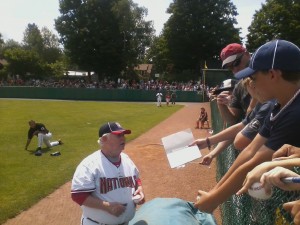

So we were out at Doubleday Field, in Cooperstown, NY, watching the 4th Annual Baseball Classic that the Hall of Fame puts on every Father’s Day weekend when one of my buddies pointed out that Jim Hannan’s name was listed in the souvenir scorecard.

“Hannan?,” I asked, incredulously. “James John Hannan, of Joisey City, New Jersey?”

I really don’t pronounce Jersey as Joisey but, well, having just come from the museum, where I saw a vintage Bugs Bunny cartoon — you know the one, where that wascaly rabbit takes on the Gashouse Gorillas singlehandedly — I couldn’t get the hare’s diction out of my mind.

“The one and the same,” my friend said.

“Is that going to be a problem for you?,” another friend asked.

“Not at all,” I replied. And it wasn’t, up until the time Hannan was introduced during the pregame ceremonies. That’s when I booed him unmercifully.

Why do I hate Jim Hannan so much, you may be wondering? I don’t hate anyone. I’ve never even met Jim Hannan.

But I do have serious reservations about his ability to be an effective advocate for the interests of the 864 men who played baseball between 1947-1979 and who are currently without pensions and health benefits.

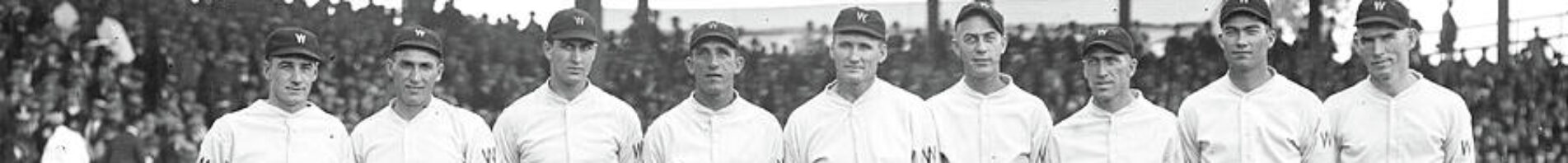

As I’m sure most of you know, Hannan, 72, is a former pitcher for the Washington Senators, among other teams he played for. Over a career that spanned 10 seasons, Hannan pitched in 276 games and compiled a won-loss record of 41-48 with a 3.88 Earned Run Average, including a career best 10-6 in 1968 when he was with Washington. A respectable career, to be sure, but nothing so glamorous that you’d be able to trade two of his baseball cards for, say, one of Frank Howard’s.

No, Hannan’s post-baseball celebrity comes from the fact that he is chairman of the board of directors of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association (MLBPAA), the Colorado Springs -based organization whose mission is to, not surprisingly, take care of baseball alumni. Fact is, Hannan’s biography on the website of the MLBPAA boasts that it was his master’s thesis which famed labor economist Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the players’ union, studied to learn about the MLB benefits plan.

Whether you take that for hyperbole or not, Hannan has a responsibility to his constituency as the chairman of the board. He should be fighting to retroactively amend the vesting requirement change that granted instant pension eligibility to ballplayers in 1980. As you may know, prior to that year, ballplayers had to have four years service credit to earn an annuity and medical benefits. Since 1980, however, all you have needed is one day of service credit for health insurance and 43 days of service credit for a pension. And while that’s obviously great for anyone whose career began after 1980, it sucks for all those men whose careers were prior to 1980.

Why isn’t Jim making his pitch to retroactively restore these guys into pension coverage? At the very least, all these men can be grandfathered back into coverage. Ask any employment benefits attorney and he or she will tell you the same thing. Heck, even Rob Manfred, the Vice-President of Labor Relations for the league, concedes it can be done in collective bargaining.

But the silence you hear out of Colorado Springs is deafening. That’s why, in my opinion, Hannan has dropped the ball.

Granted, MLB doesn’t have to do anything for these men. They’re not vested in the pension plan, and the players’ union doesn’t have to be their legal advocate. Believe me, I get that.

But if you know anything about me and the volunteer campaign I’ve undertaken the last three years, you know that this isn’t a legal issue for me. It’s a moral one based on employment law.

See, in 1993, MLB decided to award 34 veterans of the Negro Leagues and their spouses health insurance. And you know what? Props to MLB for doing that. The late Commissioner Giamatti was fond of saying, “in matters of race, in matters of decency, baseball should lead the way.”

And obviously, before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, during the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s, MLB was just a mirror institution for the social segregation that was going on in this country. So MLB did right by trying to remedy the injustices of the past.

Then, in 1997, MLB awarded 29 veterans of the Negro Leagues life annuities totaling between $7,500 and $10,000 per year. Again, I give a big thumbs up to MLB for doing that. They also awarded Caucasian men who played prior to 1947 — the year the pension fund was established — quarterly $2,500 payments.

And finally, in 2004, MLB awarded additional veterans of the Negro Leagues $40,000 for four years, or $350 a month for life.

What people fail to realize is that many of the men who are still being taken advantage of are persons of color. Herb Washington, Wayne Cage, Billy Harrell, Aaron Pointer, to name but a few….they’re all African-Americans. That’s why this issue is not a racial one for me. I’ve attempted to frame the debate from an employment benefits perspective, not a racial one. You magnanimously give health benefits to one group, you better damn well give similar and comparable benefits to those men who actually worked for you.

I’ve said on countless occasions that I didn’t open up this Pandora’s Box, MLB did back in 1993. The league opened up the door, not me, by giving health insurance to men and their spouses who it didn’t have a contractual working relationship with. So this is a matter of fairness and equity for me.

Because of all the press my book has received, MLB last April 21st announced with much fanfare that men such as former Senators Alan Koch, Bill Denehy and Carl Bouldin would receive life annuity payments of up to $10,000 per year for their service credit and contributions to the game. Each affected player is guaranteed $625 per quarter of service, up to four years, or 16 quarters. The league and union later agreed to extend these life annuity payments through 2016.

That’s not so bad, you’re probably saying to yourself. Actually, it is. A guy like Kenny Wright, who pitched for the Royals and the Yankees, and who is credited with 3.25 years of service, got a gross check for $8,125 recently. After taxes are taken out, however, his net is only $5,900. Moreover, not only can’t the payments be passed on to a designated beneficiary, spouse, child or loved one, but the retired player still isn’t permitted to buy into the health insurance coverage plan that the player’s pension fund offers its vested pensioners.

Now is that fair?

I hope that the leadership of the MLBPAA understands the urgency of getting both the league and the union to do right by these men once and for all. Hannan and the executive director of the group, Dan Foster, have to become more proactive. They could start with simply issuing a public statement in support of these men.

But I suspect they never will. Remember the DeNiro picture Bang the Drum Slowly? Well, the alumni association hasn’t banged the advocacy drum either loudly or softly. They’re just content to let MLB and the union dole out whatever bone they see fit to give these retirees.

What exactly have they done? Gary Neibauer, a resident of Aurora, Colorado who served on a special MLBPAA pensions subcommittee attempting to help the retired players, was recently relieved of his duties on that body. A former hurler for the Philadelphia Phillies and Atlanta Braves, Mr. Neibauer and former Texas Ranger pitcher David Clyde are widely credited with having prodded Mr. Foster into monitoring negotiations between the league and the union. Mr. Clyde was relieved of his duties as well.

Word is, the alumni association wanted to get younger folks on this committee and, well, Clyde is all of 57. As for Neibauer, he is going to turn 68 this October.

Jeez, that’s positively ancient. Meanwhile, Eddie Robinson, the former All-Star first basemen, coach, scout and general manager who spent all of 1949 and part of 1950 with the Senators, is going to turn 92 this December. Yet he’s still on the committee.

Now does that sound fishy to you? Me too. That’s why I don’t have great expectations for Jim Hannan. Seems like all he and the alumni association board just want to do is uphold the status quo.

But don’t believe me. As one of the pension committee members told me in an interview for my book, “Hannan is wishy-washy,” he said. “He’s got a spine like a piece of spaghetti.”

Hey, it could be worse. As pastas go, he could have compared Hannan to vermicelli instead.