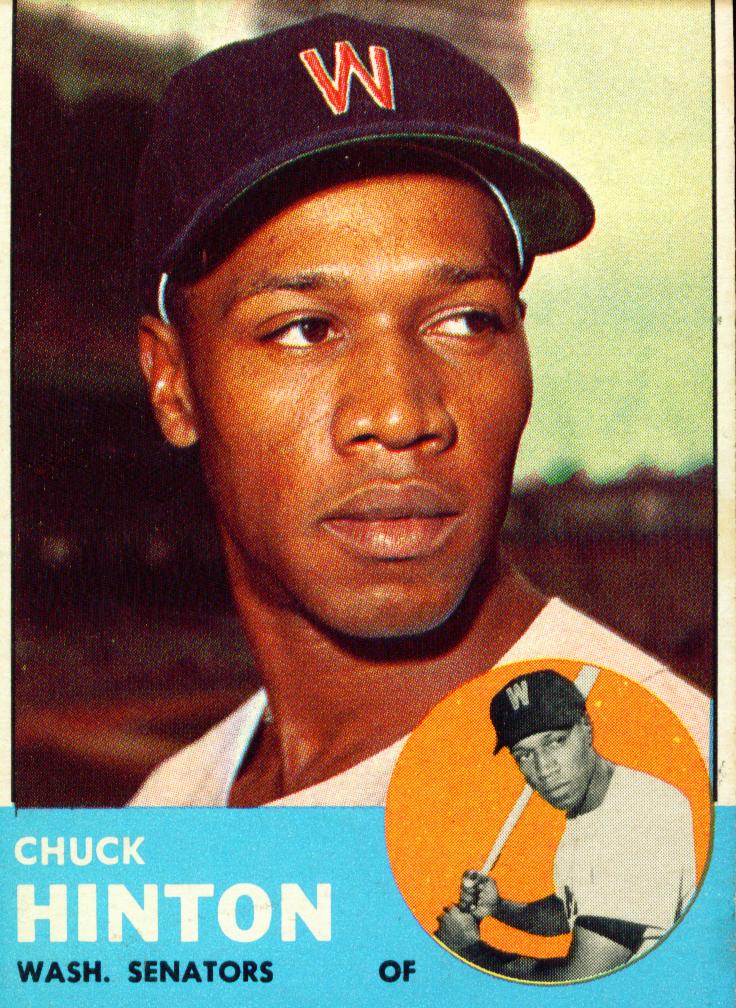

Chuck Hinton was indeed, one in a million. I first met Chuck in the mid-1990s while I was writing my book on the expansion Senators. I asked him if he would allow me to interview him for the book. I was surprised and thrilled  when he said, “yes.” This was one of my first “up-close and personal” meetings with a former major league baseball player and I began the interview with more than a slight case of nerves. Frankly, I was in awe to be sitting across from the last Washington Senators player to hit .300 and someone I cheered for during my early teens when Chuck patrolled the outfield at Griffith Stadium and the new D.C. Stadium. Chuck made me feel that no question was too trivial, and we spent what must have been the better part of an hour talking about his eleven-year career with the Senators, Indians and Angels. But there was much more to Chuck Hinton than his career as a major league baseball player.

when he said, “yes.” This was one of my first “up-close and personal” meetings with a former major league baseball player and I began the interview with more than a slight case of nerves. Frankly, I was in awe to be sitting across from the last Washington Senators player to hit .300 and someone I cheered for during my early teens when Chuck patrolled the outfield at Griffith Stadium and the new D.C. Stadium. Chuck made me feel that no question was too trivial, and we spent what must have been the better part of an hour talking about his eleven-year career with the Senators, Indians and Angels. But there was much more to Chuck Hinton than his career as a major league baseball player.

For 28 years, Chuck was the head baseball coach at Howard University. During his career at Howard, Chuck coached such media luminaries as Gus Johnson of CBS Sports and Glenn Harris of News Channel8 in Washington. During Chuck’s tenure, Howard established records for most games won and most MEAC championships. All of the Howard championships came while Chuck was working full-time for the D.C. Department of Recreation as a Roving Leader to D.C.’s at-risk youth. As if those accomplishments weren’t enough, Chuck, Jim Hannan and Fred Valentine were the forces behind the establishment of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association. Thanks to the MLBPAA’s efforts, former major leaguers who previously were declared ineligible for pensions because they lacked the necessary years of major league service, are now receiving pension checks. I was in awe not only of a baseball player, but of someone who tirelessly gave of himself.

The Chuck Hinton that I had watched as a child became the Chuck Hinton of my adult life. We ran into each other several times over the years at a variety of venues from Bethesda Big Train baseball games to (of all places) Arena Stage where Tom Holster, Hank Thomas, Chuck and I served as “historical advisors” for Arena Stage’s 2005 production of “Damn Yankees.”

Chuck was a guest at two of the Washington Baseball Historical Society’s player reunions that were called “Nats Fests.” He was a frequent guest at memorabilia shows and charitable events around the D.C. area and beyond.

Whenever our paths crossed, Chuck would always greet me with a warm smile, a handshake and ask the same question: “When are you going to have another one of those reunions?” He seemed to have the rare quality of making everyone he met feel like a good friend. On Opening Night at Nationals Park in 2008, I was on the upper concourse when I heard someone shout, “Hey Jim!” I turned around and there was Chuck, smiling, as usual. The simple fact that he would take the time to say hello to me completely blew me away. But that was Chuck Hinton.

The baseball seasons passed and the Nationals were playing poorly, but Chuck was often at the ballpark, sitting in the final row behind Section 110. I always took the time to stop by and say hello, and we would talk about the Nats and any other thing that came to mind. But during the 2012 season, every time I stopped by Section 110 to say hello, Chuck was not in his usual spot. I prayed that he wasn’t having a recurrence of health issues that had bothered him in previous years.

When Chuck decided to write his autobiography, “My Time At Bat,” in 2002, I spoke often with his daughter Kimberly who was handling the publication of the book. I offered her any help I could provide to make the process easier and offered any publicity she needed in “Nats News.” When I received an e-mail from Kimberly on Monday morning and saw the subject line, I felt an immediate sense of loss. My fears had been confirmed. Kimberly wrote that her father had passed away on Sunday, January 27.

Chuck Hinton was a kind, gentle man who made a difference in the lives of everyone he met. I know that whenever I walk past Chuck’s section at Nationals Park, I’ll still be looking for him.