“Get Philadelphia”

That was the motto of the Senators 1926 spring training session in Tampa.

In 1925, the young and enthusiastic Philadelphia Athletics surprised the experts with a strong hitting attack and deep pitching staff, and by holding first place into August before the pressure of the pennant unraveled the team and sent them into a tailspin, which knocked them out of contention. Now, one year later, the A’s were a year older and wiser and the overwhelming choice to dethrone the two-time league champion Senators.

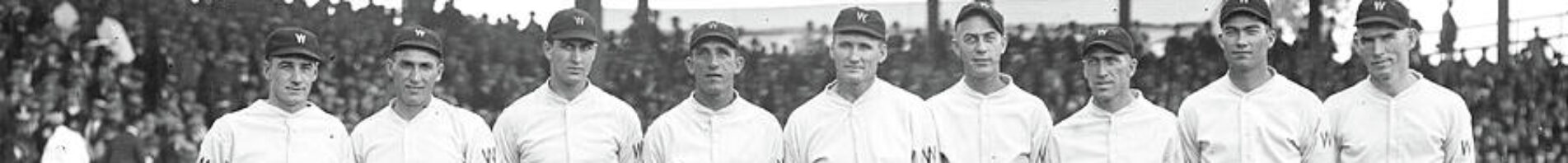

Content with the team that had won American League pennant for the second year in a row, the Senators stood pat on their veteran squad, but did have a few new players, including the highest rating minor league player in 1925 to prove the old saying of the rich becoming richer.

Tabbed as a can’t miss rookie, there was talk about the youngster moving ahead of 1925 league MVP Roger Peckinpaugh to become the team’s starting shortstop.

According to Washington’s super scout Joe Engel scouting report, the prospect could do it all: hit, field, cover ground, and run like the wind.

The path for the Senators to obtain Buddy Myer was anything but simple. But in spite of the red tape and competition from other ball clubs to get Myer, Washington was fortunate to land him for a reasonable cost of $22,500, two veteran pitchers, and the promise to let the kid sensation finish the 1925 season with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern League.

Born in 1904 in the baseball crazy town of Ellisville, Mississippi, Buddy Myer had switched off at all the infield positions while playing in the local sandlot leagues. But that changed when he entered Agricultural High School and settled on one position: “I found myself at shortstop.” In 1921, he and several of his high school classmates enrolled at Mississippi A & M College (now Mississippi State) where he starred on the diamond from the beginning. During his sophomore season, the Cleveland Indians scouted Myer and expressed interest in signing him. Following his sophomore season, he spent a few weeks with the team before telling him he wanted to complete college, but gave his word that he would be back. True to his word, Myer rejoined the Indians in spring training in 1925. Wanting to sign the shortstop and send him to Dallas for seasoning, the Tribe offered a contract. Myer was okay with Dallas, but insisted on a $1,000 bonus during a time when it was unheard of and considered to be rude for an unproven collegian to request a signing bonus. Team manager Tris Speaker answered by sending Myer back to Ellisville without a contract.

Joe Engel, who had discovered Myer before informed that the Indians had a verbal agreement, was in Little Rock when he heard the news and the reason why Myer was unsigned. The scout immediately acted by contacting Griffith for his consent on paying the $1,000 signing bonus. He then traveled to New Orleans to catch a train for Ellisville, but while on his way to Ellisville, Myer was on a train heading in the opposite direction. When Engel arrived at the Myer residence on Court Street, he was updated by the ballplayer’s family. He then traveled back to New Orleans, but arrived at the ballpark a minute after Myer had signed his contract (and received a check for his signing bonus). Engel and the Senators would seal the deal for Myer by the end of May, but for a substantially higher cost than what could have been just a $1,000 singing bonus.

The saga with Myer wasn’t over. In August, Griffith contacted the Pelicans to inquire why Myer’s name was not appearing in the daily box scores. The Pelicans responded by reporting he was ill, but would be back in the lineup soon. But when “soon” passed and Myer’s name was still absent from the boxes scores, New Orleans was forced to confess that Myer had sustained a spike wound, which was improperly treated, developed into blood poisoning, and surgery was required. Both of Myer’s legs were cut to drain the poison. When that did not work, his right leg was cut a second time.

Griffith ordered Myer to be sent to Washington right away. The problem was Myer was so ill and weak and in need of rest, he was unable to get out of bed.

Myer was still ill when he finally felt strong enough to travel to Chicago to meet the Senators. Under the care of Senators trainer Mike Martin, Myer was nursed back to health and back on the field in time to debut with the Senators before the end of the season. Now in the spring of 1926, Myer was healthy and ready to go.

Roger Peckinpaugh was still hurting from his leg injury sustained late in the 1925 season. He was in Hot Springs when spring training had begun, and told by Griffith and Harris to stay there as long as he needed in order to get himself ready for the upcoming season. The Senators were relying on the 1925 MVP for 1926, and they wanted to be sure he was in tip-top shape.

There were a few other new faces in Tampa. Bullet Joe Bush and Jake Tobin had come from the Browns in exchange for pitchers Tom Zachery and Win Ballou. Left-handed Tom Zachery was a good Senators hurler, winning twelve games in 1925 and fifteen and two World Series games in 1924, plus was three years younger than Bush. But perhaps Harris believed the Nats could catch lightning in a bottle with Bush in 1926 like they had with twenty-game winner Stan Coveleski in 1925. A longtime star with the Yankees, Bush had been traded by the Yanks to the Browns before the 1925 season. With the Browns he went 14-14, but showed flashes of talent by hurling a shout out against the Yankees and a one-hit shutout over Washington.

Outfielder Jake Tobin was thirty-four and owned a .311 lifetime batting average. Harris hoped to get him some starts in right field, but his plan was to primarily use him as a pinch-hitter.

The weather in Tampa was cold; the coldest spring in thirty years according to the oldest city residence. It was so cold that the players huddled around the fireplace in the hotel lobby during the evenings. The unseasonable weather forced Harris to alter his plans. Worried the conditions might re-aggravate Peckinpaugh’s ailing leg, the manager was forced to go with Myer at shortstop, and the rookie responded by hitting .400 and handling 47 of his 52 fielding chances through the first ten exhibition games.

“Harris is satisfied as Myer forces Peck out of starting job,” read the headlines in the Washington Post.

Frank Young of the Washington Times opined that Myer was a better mechanical fielder than Peckinpaugh based on his speed and ability to cover more ground.

James Harrison of the New York Times asked Harris is he intended starting Myer instead of Peckinpaugh.

“I have no intention on benching last season’s Most Valuable Player,” Harris responded with some excitement. “We’re not the same team without him.” Perhaps that was a reason why the Nationals suffered through a tough exhibition season.

In a game versus the Phillies at Plant Field in Tampa, the Senators committed five errors in a lopsided loss. The fans, disappointed with the team’s performance, began to boo Harris and his team. “Let ‘em rave,” responded Harris. “I know we are not playing a good game. But their raving is not going to help us play any better, or worse.”

But little did those Tampa fans know that Harris was as unhappy with is team as they were. As the team began to head north to continue their exhibition season, the manager held a team meeting before a game in Birmingham. “I want more pepper on this cub,” he told his team, “and I will have it before the American League season starts.”

Harris must have felt that his team would regain the fire he wanted. He felt confident enough to tell the writers that his team would win a third consecutive pennant in 1926: “They couldn’t beat us in 1925 and I don’t see any club that has strengthened enough to beat us in 1926.”

But the Washington manager was among the minority in thinking the Nats would win again. Most experts looked at the ages of the Washington pitching staff and noted they were all a year older. In addition to Johnson now at age thirty-eight, Coveleski was thirty-four, Bush was thirty-three, and Ruether was thirty-two. “The Senators pitching staff has a higher age than the U.S Senate,” wrote James Harrison.

Babe Ruth, who was hungry to regain his superstar status, also chimed in by picking the Yankees to win the pennant and added that the Washington “Senators will be lucky if they finish fourth.” As for the 1925 Nats, Ruth said, “They picked up some old fellas who happened to come through for them.”

Harris had a response for Ruth: “My team is not composed of old men. It is made up of the best ballplayers ever produced.”

Washington concluded their 1926 spring season with a ten game series with the New York Giants. Like the World Series from the previous fall, Washington dropped the last three games of the series and settled for a five-games-to-five split. Following the last game, which was at Griffith Stadium, a few of the Senators expressed their anger in the clubhouse to sum up what had been a long and frustrating exhibition season.

1926 Washington Senators – Part One

Gary is the author of The Wrecking Crew of ’33; The Washington Senators’ Last Pennant. Gary has written for Nats News, Minor League News, and for the Biography Project of the Society for American Baseball Research. He lives in Arlington, Virginia.