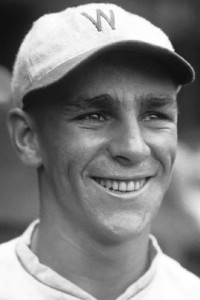

Senators scout Joe Engel had on eye on a shortstop at Georgia Tech throughout the spring. So did the Indians and Braves, but Engel was the one who got the collegian’s signature on a contract.

Bobby Reeves was a terrific all-around athlete from Chattanooga. At Georgia Tech he starred on the football and

baseball, and now he was on his way to Washington to begin his major league career. He did have one request before heading to Washington with Engel: he wanted to play in the last two ball games of the college season; and for a good reason. It was for the championship of the southern colleges.

Reeves and the Engineers defeated rival Georgia in both games.

The Senators made it clear that the signing of Reeves had nothing to do with Myer’s disappointing start, but as an opportunity to sign a good player with a bright future.

Reeves looked good at the plate and showed good speed on the bases during a pre game practice with the Senators. But in the field he appeared to be rather shaky. In addition, he had a very peculiar underhanded throwing style. The consensus was Reeves needed lots work before he could play in a major league game. Figuring it was better to tutor him while practicing with the team rather than sending him to a minor league team, the Senators decided it was best to keep him on the club.

Washington’s first place lead lasted for a few days. When Ty Cobb and the Tigers made their first appearance of the season at Griffith Stadium on May 19th, the Nats had lost 3 of their last 4 to fall from the league’s top spot. It became 4 losses in 5 games when the Tigers blanked Washington, 6-0, with Bush taking his fourth loss of the season.

The veteran Bush was wild. He had hit 3 batsmen, including the opposing pitcher, Augie Johns. After Johns fell to the ground in pain as the third Tigers batter to be hit-by-a-pitch, the voice of Ty Cobb was heard from the Detroit dugout. Bush responded by turning to the Tigers bench and shouting back at Tigers’ manager.

Cobb went 3 for 4 on the day and gave a great demonstration to on how to execute a delayed steal when, with Senators rookie Bill Morrell now pitching in relief of Bush in the top of the ninth, Cobb wondered off the first base bag and began to pace toward second base. Washington reserve catcher Hank Severaid and Bucky Harris began to shout at Morrell. Cobb reacted by turning his walk into a sprint. Morrell quickly wheeled and threw to Harris who was covering second base. Knowing the throw was going to beat him to the base, Cobb started to put on the breaks until noticing the throw was high and wide. Cobb then put on the burners, slid to side of the base that was opposite of the throw, and beat Harris’s tag.

The two teams split the next two games, but rather mysteriously was that manager Harris was plunked in both games, perhaps in retaliation for three of Tigers hitters being hit.

Harris and Cobb shared no love for one another. Two years before, while the two teams battled in a close pennant race, Cobb did what he could to get Harris’ goat through insults. Perhaps a way to give it back to Cobb, the Senators raised their 1924 World Championship banner on a day when the Tigers happened to be in town during the 1925 season.

The Senators continued to slump through the second half of May. Three consecutive losses to the A’s dropped them to fifth place and 9 ½ games behind the first place Yankees. Needing a win against Boston, Harris took matters into his own hands to pull out the victory. With the bases loaded in the bottom of the eleventh in a tie game, Harris leaned into an inside pitch to force in the winning run. Later that evening, Harris was having dinner with his fiancés Elizabeth Sutherland and her father when his bride-to-be when the subject of the game’s winning run came up. “If I did not know better, I thought you let that ball hit you,” Miss Sutherland said.

“Stanley would never do a thing like that,” added Mr. Sutherland.

Not wanting to disappoint his company, Harris said the hit-by-pitch to end the game was purely accidental.

The enthusiasm over Peckinpaugh’s return to the starting lineup had fizzled. The veteran shortstop was hitting just .222, and perhaps a sign of age, his legs were taking longer than expected to regain its full strength. Figuring that Myer’s speed would help, Harris inserted the rookie back into the starting lineup, at third base. Ossie Bluege, switched from the hot corner, became Washington’s third shortstop of the season.

Myer’s bat began to show signs of life, but his fielding continued to suffer. An error and a mental mistake in the same game led to him being benched in the middle of the contest. “Myer’s failure keenest disappointment of the year,” wrote one Washington sportswriter. Peckinpaugh was sent back into the lineup and Myer once again found himself on the bench.

The Senators began June at Yankee Stadium to face the seemingly unstoppable Yankees. The first place Yanks were hitting .321 as a team, their big three – Hoyt, Pennock, and Shocker – were a combined 21-3, and Babe Ruth was hitting .380 with 16 home runs. And they further damaged the Washington pennant hopes by taking both games of the two game set. “The Nationals now appear to be only a shell of a once great ball club,” wrote a writer from the Washington Star.

At the core of the team’s problems was the fall of their defense and pitching staff. Harris was also becoming increasingly upset over what he believed to be a lack of team spirit, especially by his veterans. But pitching was the team’s number one concern. Walter Johnson, who began the season by winning 6 of his first 7 decisions, had now lost six in a row. Stan Coveleski was also having a mediocre season, but the biggest enigmas were Bullet Joe Bush and Alex Ferguson.

Bush was now 1-8 with a 7.42 ERA, while the two pitchers he was traded for, Tom Zahery and Win Ballou, were doing well in their new surroundings at St. Louis. Ferguson, 4-1 after being claimed on waivers by Washington during the tail end of the 1925 season, and won a game in the 1925 World Series, was now performing at the same sub par level he had displayed throughout most of his career. Bush was put on waivers. “He has been unable to win for us,” Said Griffith. Ferguson was sold to a minor league club (Buffalo), and manager Harris issued an SOS to Joe Engel. “Get pitchers, if they are to be found.” Engel hit the road in search of experienced pitchers rather who could help the club now instead of prospects for the future.

“I have a southpaw (pitcher) who ought to be in the big leagues,” Columbus manager Hank Gowdy had told Harris during spring training. Engel acted on a tip and paid a visited to Columbus, Ohio. He looked over the hurler, decided that Gowdy was right, and arranged for the purchase of thirty-one year-old Cuban lefthander Emilio Palmero, who had once pitched for the Giants and Browns during two partial seasons in the majors. But Palmero proved unimpressive. He pitched in 7 games for Washington, walked 15 batters in 17 innings, and Griffith decided that the veteran southpaw would not do.

Engel found three good pitchers in the Southern League, beginning with twenty-seven year-old George Murray at Mobile, who once had a stint with the Yankees and Red Sox. He was having a mediocre season in the Southern Association, but Engel felt he would do. Another twenty-seven year-old pitcher was found in Memphis. Unlike the other two signed pitchers, Hod Lisenbee had no prior major league experience. He was 17-9 at Memphis in 1926, although would be unable to play for Washington this season due to being ill.

The prize of Engel’s scouting trip was a pitcher at Birmingham who would eventually became a star with the Senators. In order to obtain the right-handed pitcher with a 17-4 season record, the Nats traded Curly Ogden and Palmero to the Barons, and Alvin Crowder, better known as General Crowder, was on his way to Washington.

Twenty-seven year-old Crowder learned to pitch when in the Army while stationed in the Philippines. He was a shortstop until one day when the pitcher from his unit complained he had a sore arm. Crowder took his place, and was a pitcher ever since. When transferred to California, he pitched for the Army team, often facing the Navy team, and once posted nineteen consecutive wins to draw the attention of the San Francisco Seals. After a year with the Seals of the Pacific Coast League, he was purchased by the Pittsburgh and reported to the 1926 Pirates spring training camp. One day in camp he took a shoulder to the ribs when colliding with Pie Traynor when going for a pop fly. The play left him injured, effected his pitching, and he was eventually released to Birmingham. Now with a 17-4 record, the Pirates were interested in re-obtaining him, but Griffith beat them to the punch.

The disappointing Senators returned home from their first road trip through the Midwest in sixth place and with a 28-31 season record. Two days later, they trailed the Yankees at Griffith Stadium by a score of 7-2 as the game headed into the bottom of the ninth. Before Washington came up for their last at bat, the megaphone announcer announced that there were plenty of seats available for the next home game. The crowd replied with a Bronx cheer. The crowd was even louder in expressing their disapproval when Bucky Harris stepped to the plate with a man on first and nobody out.

The manager singled, and then Goslin surprised everyone by laying down a bunt for a hit to load the bases. All seemed lost when Joe Harris bounced into a 1-2-3 double play, but hope was reinstated when Judge walked, and Bluege and Peckinpaugh came through to score two runs to make it a 7-5 game. Then Yankees outfielder Bob Meusel missed on a shoestring catch try which resulted in a 3-run misplay and an 8-7 Washington win.

The Senators went on to sweep the Athletics in four straight to move over 500, but were still in sixth place and thirteen full games behind the Yankees.

Roger Peckinpaugh’s days were numbered with the Senators and for his brilliant career. The thirty-five year-old wasn’t hitting, was making errors, and couldn’t cover the ground he once was able to. On June 30th the veteran shortstop was running out a ground ball. When he crossed the first base bag he let out a yell, began to limp, then sat on the ground as he clutched the back of his leg. He had pulled a hamstring, and he would be sidelined for a few days. But when he returned, he was informed he would be riding the bench and serve as Myer’s backup for the rest of the season. Washington was now rebuilding, and Myer represented the next era.

Disappointed and hurt by the demotion, Peckinpaugh made the best of it rather then complain. He settled on serving as the first base coach, hoping this would be a step in managing within the next few years. One month later, the Nats asked for waivers on Peckinpaugh, however, when claimed by the Yankees, Washington quickly reclaimed the 1925 MVP.

1926 Washington Senators – Part One

1926 Washington Senators – Part Two

1926 Washington Senators – Part Three

1926 Washington Senators – Part Four

Gary is the author of The Wrecking Crew of ’33; The Washington Senators’ Last Pennant. Gary has written for Nats News, Minor League News, and for the Biography Project of the Society for American Baseball Research. He lives in Arlington, Virginia.