The two-time defending American League champs continued to play mediocre baseball at the beginning of the season’s second half. Manager Harris assured the sportswriters that the pennant race was far from over and the Nationals still had a solid chance. But after the fifth place Senators lost to Cleveland on July 19th, they fell ten games behind the first place Yankees.

Harris believed a big part of the problem was in the lackadaisical attitude displayed by several veterans. Since spring training he had demanded more team spirit. Four months later, the boss was still not getting his order fulfilled, and now was fed up to the point where he issued a warning: “Either you give the game everything you can or suffer the consequences,” he told his team. The next day Goose Goslin found out the hard way that his manager meant business.

The first three players had reached base for Detroit in the top of the first. The fourth batter of the inning, Harry Heilmann, hit a pop up to leftfield. Goslin loafed and played the pop fly into a hit on what should have been a catch. The Tigers went on to post five runs in the inning. When the Nats entered their dugout following the conclusion of the inning, Harris informed Goslin to get out.

Goslin was suspended, indefinitely.

The Tigers went on to win the game, 7-6. Washington took the nightcap, 10-7, and won the following day, 13-10, with Goslin viewing the game from the stands.

The fourth game of the series was played before a Friday ladies day crowd on July 23rd. It was the day before the Senators planned to raise their 1925 championship banner, and for the second straight season, they would be presenting their championship banner in the presence of Cobb and his Tigers. But Cobb had a plan to dampen the spirits for the occasion.

In the first inning, the Tigers fiery manager bawled out his catcher for permitting Sam Rice to steal second base. The fans began to boo to express their displeasure in the Detroit manager’s temperament. A few innings later, the Detroit manager was on the field to protest a ruling by the umpire, when suddenly he took off for the stands (Later claiming he was hit by a bottle). He stopped short of the dugout to give an unfriendly oration to the crowd. According to the fans closest to the field, Cobb was not using the kind of language heard during Sunday school, and it was most inappropriate before a ladies day crowd. After he finished his speech, Cobb walked across the field to Griffith’s box to the sound of boos and catcalls. When he got to Griffith’s box, he asked the Washington owner for “protection.”

“Protect yourself and I’ll look after the fans,” Griffith told Cobb. (It was reported that Griffith meant for Cobb to “control himself,” and he would handle the crowd).

A policeman was stationed next to the Tigers dugout for the rest of the game.

Cobb was not finished. Later in the game he engaged in an argument with his first baseman, Lu Blue, then informed him that he was taking him out of the game. As Blue walked passed the section of sportswriters behind home plate while on his way to the clubhouse, he was heard to mumble something about being finished with playing for Ty Cobb and the Tigers.

Following the conclusion of the game, Griffith dispatched a telegram to Ban Johnson, the American League President, to complain about Cobb’s inappropriate behavior. Ban Johnson responded by ordering the umpire crew to remove Cobb from the game if he was to engage in the same manner of behavior the following day, but Cobb, perhaps knowing that repeat actions would not be tolerated, was on his best behavior.

The next day, General Crowder made his debut with the Senators. He pitched a complete game, allowed just one unearned run, and permitted only one walk in a tough 3-2 loss to the Tigers. In the top of the fifth, Tigers outfielder “Fatty” Fothergill disagreed when called out on out strikes. He verbalized his dislike over the called third strike, heaved his bat, and was ejected. As he continued to argue, manager Cobb walked over from the third base coach’s box. The Detroit manager played the peacemaker role, was able to calm his angry outfielder and lead him away. A few innings later, Tigers pitcher Earl Whitehill barked at the home plate umpire about his calls on balls and strikes. Cobb emerged from the dugout, headed to the pitcher’s mound, and was able to calm his hurler. An inning later, with Detroit at bat, an old man rose from the box seats behind the Tigers’ dugout and began to shout to the crowd about his dislike for the Detroit manager. As the crowd laughed along, “the senile” old man began to shout at Cobb, who was in the third base coach’s box. Cobb heard the excitement, turned around to look, and then cracked a partial smile when looking at the elder fan. He then turned back to face the action.

A few weeks later, when the Senators were in Detroit, Cobb was at it again. Walter Johnson homered off of Detroit pitcher Augie Johns. Cobb responded by removing Johns from the game, and the Tigers hurler retaliated by heaving the ball into the outfield.

Walter Johnson’s best days were behind him. He had a great start to the 1926 season by winning six of his first seven decisions, but cooled off in a hurry by dropping seven straight decisions to fall to 6-8. He was 11-10 for the season when he started versus the Browns at St. Louis on July 31st, with the disappointing Senators in sixth place with a 48-47 record, but on this day, Sir Walter blanked the Browns for his 112th career shutout.

The ten games following the shutout were indicative of the kind of season the Senators were having. They scored 75 runs, but the pitching staff yielded 69 runs, an average of almost 7 runs per game. The frustration of the season was summed up by Goose Goslin, who was hitting .459 since being reinstated. “Every time I ‘bust’ one for four bases, the other club always manages to come through with a rally that makes my hit as useful as a sieve for eating soup.”

Goslin’s words were taken to heart by some, and it added to the dissention that already existed on the club.

Manager Harris was feeling the frustration more than any Washington player, or fan, and showed it in a game versus the Yankees on a sweltering hot day in mid-August when the Washington manager argued with umpire Brick Owens on a call at second base. When Owens decided that the debate was done, he turned and began to walk away. Harris reacted by grabbing the arbitrator by the jacket. The Washington manager was ejected and suspended and fined. (However, the suspension would be lifted).

The misfortunes of the Senators continued through August. Although the team was leading the league in hitting, other factors had dropped the two-time league champions into mediocrity. Dissention was one problem. Age catching up to the pitching staff was the biggest problem. Johnson’s brilliant career was now drifting into the twilight. Coveleski, a twenty-game winning the year before, was 9-10 in mid-August, and like Johnson, was nearing the end of his career. Dutch Ruether had a 12-6 record with a high ERA, but had lost his stuff and no longer could throw an effective curve. “I just mixed ‘em up- fast ones and slow one,” and he was sold to the Yankees.

The lack of a reliable fielding shortstop was also a factor in the team’s decline, beginning with the demotion of aging Roger Peckinapaugh to the bench. The glue of the Washington infield through his leadership and fielding skills was affected by his ailing knees. Knowing his best days were behind him, the Senators waived Peckinpaugh, but withdrew waivers when the Yanks claimed him.

Buddy Myer proved he could hit after all and was inserted into the cleanup spot of the batting order, where he hit .357 during one stretch to boost his season average over .310. But in the field he struggled in turning double plays, couldn’t throw on the run, and showed an inability to go to his right. He was clearly a liability in the field, and Bobby Reeves, the other shortstop hopeful of the future, still needed more time to develop.

On August 23rd, Washington lost at home to the Browns, 8-4, to fall to 59-59 on the season. It was now time for the Senators to think about 1927 and the future.

1926 Washington Senators – Part One

1926 Washington Senators – Part Two

1926 Washington Senators – Part Three

1926 Washington Senators – Part Four

1926 Washington Senators – Part Five

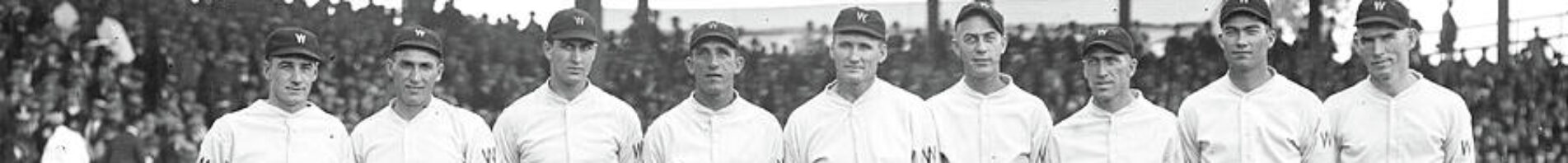

Gary is the author of The Wrecking Crew of ’33; The Washington Senators’ Last Pennant. Gary has written for Nats News, Minor League News, and for the Biography Project of the Society for American Baseball Research. He lives in Arlington, Virginia.