So many years have passed since the nation’s capital last hosted baseball’s All-Star game that most people have  forgotten the unique, unforgettable events that took place before and during the 1969 midsummer classic as well as one of the many fiascos one Robert E. Short committed during his sad, incompetent tenure as the Washington Senators’ final owner.

forgotten the unique, unforgettable events that took place before and during the 1969 midsummer classic as well as one of the many fiascos one Robert E. Short committed during his sad, incompetent tenure as the Washington Senators’ final owner.

In 1969, baseball intended the all-star game to be the grand finale of its celebration of baseball’s supposed centennial, marking the 100-year anniversary of the first professional club, the Cincinnati Reds. To honor the occasion, baseball named the greatest starting nine from each franchise in the days leading up to the all-star break.

The night before the scheduled game, baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, in his rookie year, hosted a black tie event at the Washington Hilton to announce the all-time greatest team, baseball’s greatest player of all-time, and baseball’s greatest living player. Babe Ruth was a lock for the greatest of all time.

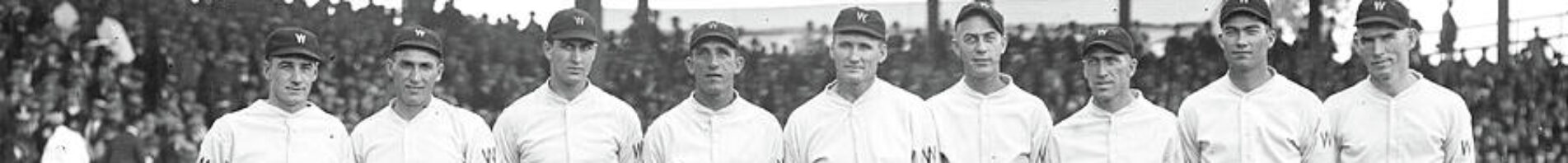

The all-time team was Lou Gehrig, Rogers Hornsby, Honus Wagner, Pie Traynor, Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Ty Cobb, Mickey Cochrane, Lefty Grove and Walter Johnson.

The greatest among those still living: Stan Musial, George Sisler, Charlie Gehringer, Joe Cronin, Traynor, DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, Bill Dickey, Grove and Bob Feller.

Fans and sportswriters alike expected the honor for the game’s greatest living player to be a two man race between Yankee great DiMaggio and Senators’ manager, Williams. The evening before the black tie gala, news reports revealed that, once again, Joltin’ Joe had gotten the best of Teddy Ballgame. DiMaggio, like all mortals not named Ruth a lesser hitter than Williams, but a better all-around player with multiple World Series rings to his rivals zero, would be named the greatest living ball player.

Williams, with a well-known disdain for stuffy formal affairs, decided not to attend the centennial celebration. Many surmised the Splendid Splinter skipped the shindig in a fit of pique over losing out to rival DiMaggio yet again. Williams’ wife, Dolores, who attended in his place, claimed her husband felt no ill will toward baseball, DiMaggio, or the sportswriters who chose the Yankee Clipper over him. She said missing the affair was just “part of his image.”

In any case, the celebration went on without Williams, who, the previous week, had been named an all-star coach by American League manager, Mayo Smith of the Detroit Tigers. Washington’s manager did attend the morning reception President Richard Nixon held for all Hall of Fame members in Washington, D.C. to take part in the all star festivities. A tuxedo-clad Williams, a one-time U.S. Marine, did not want to show disrespect to the nation’s Commander-in-Chief.

As Washington sweltered through another steamy day in a summer long heat wave, current players prepared for the big game to take place later that evening, Tuesday, July 22, 1969. Unfortunately for those with tickets to the game, nature had other ideas. Late in the afternoon, a classic Washington area thunderstorm erupted. Buckets of rain poured down amidst the thunder, hail, and lightning.

Most storms like this in D.C. last a few minutes or so. The storm of July 22, 1969 was different. The thunder and lightning ceased, but the rain still fell, and fell, and fell.

RFK Stadium sat in the thick of the storm. Water drenched the field before any covers could be put in place. Waterfalls cascaded, flooding both dugouts. No amount of effort by Groundskeeper Joe Mooney and his crew could forestall the awful news. The game had to be postponed or outright canceled.

Kuhn huddled with his lieutenants and made Mooney and Short an offer. Everyone could alter their travel arrangements to squeeze the game in on one condition — Mooney had to have the field in playable condition by the next afternoon.

Fans greeted the news the game might be played with mixed emotions. Many had no way of missing work for a Wednesday afternoon game, that might not be played anyway. Some of these poor folks had already braved Short’s gross mismanagement of the distribution of 20,000 tickets MLB had made available for public sale.

Baseball delegated the job of selling these tickets to the Senators. The club announced that tickets would be sold starting Monday, July 21, at 9:00 a.m., from two windows at the stadium. Fans from the D.C. area lined up at the crack of dawn for a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see baseball’s best. Despite the stakes, the crowd milled around peacefully, everyone respecting his neighbor’s place in line.

The clock struck nine and Short’s ticket sellers arrived at their stations. Suddenly, windows opened at six locations, not the advertised two. With four unexpected — and empty — windows available, the once docile crowd broke ranks and a near riot ensued.

Former fast friends pushed past each other, cut in line, and did whatever they could to get their hands on some tickets. As Senators’ employees frantically sold tickets as fast as they could, no one from the team showed up to try to restore order or alert police to the situation.

Soon, all the tickets were gone. The sellers locked their windows and huddled inside, waiting for the angry mob to disperse. Senators’ fans who had missed work, excused or not, to arrive early went home empty-handed. And now, because of the weather, those who did get tickets, by ways fair or foul, also had to take off work another day to see the game or try to sell their game passes to friends of the highest bidder.

Washington Post sportswriter William Gildea, took the team to task for their incompetence, calling the situation a fiasco, which it certainly was. Lots of people who deserved to witness the game ended up ticketless and angry at the Senators’ organization. It may well be that some readers of this blog were victims of Short’s shoddiness.

Finally, on a warm, sunny Wednesday afternoon, July 23, 1969, after round-the-clock work by Mooney and his crew, the 1969 All-Star game began. The affair featured 20 men who would eventually become members of the Hall of Fame. Here is a link to retrosheet’s starting lineups, box score, and play-by-play account of the game: http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1969/B07230ALS1969.htm

The players were introduced one by one, as the crowd roared with excitement. Only Willie Mays‘ standing ovation approached the duration and volume of the roars for Washington’s own, Frank Howard. Darold Knowles, the Senators’ other all-star, despite starting the season in late May due to military service, received a warm welcome as well.

Yankees’ ace Mel Stottlemyre started the game for the American League. The National League, who dominated the midsummer classic throughout the 1960s, raced to a 1-0 lead courtesy of a Frank Howard error. Hondo was nervous playing in front of his hometown friends.

A Johnny Bench home run added two more to the NL’s lead. Then, with one out in the bottom of the second inning, the massive Howard, the Capital Punisher, strode to the plate. Steve Carlton stood on the mound, a hard throwing lefty, the kind of pitcher Howard liked to hit against.

Carlton threw his trademark fastball and Howard made history. He smashed a tremendous line drive to right centerfield. The ball climbed quickly, almost violently, rising higher and higher. The ball eventually landed in the upper deck, nearly 500 feet from home plate. Here is a link to video of Hondo’s blast (fast forward to the 3:14 mark):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W_Ytcb8eBNs&feature=youtube_gdata_player

The sell out crowd roared. Howard circled the bases quickly and humbly, honoring baseball tradition, but his heart soared. He knew he had given all who love baseball in Washington a memory for the ages. Nearly 40 years later he said, “Anytime you can do something like that in front of your people, your city, your fans, it’s something I’ll always treasure. I try not to live in the past, but it’s sure nice (when people remember you).”

Once Oakland’s Blue Mood Odom entered the game, replacing Stottlemyre, the NL broke the game open with a 5-run rally. Willie McCovey‘s 2-run homer following a Hank Aaron single, was a highlight of the outburst. After a Carlton double gave the NL an 8-1 lead, Smith removed Odom for Knowles.

Washington’s own ace lefty reliever stopped the rally, retiring Matty Alou and Don Kessinger on ground outs. Knowles recalled the moment as his second most cherished baseball memory, surpassed only by getting the final out of the 7th Game of the 1973 World Series, a series in which he appeared in every game for the Oakland A’s.

In the 4th inning, Howard walked and left the game, to loud boos from the D.C. crowd, for pinch-runner Reggie Smith of the Boston Red Sox. The game featured other great moments. McCovey blasted another homer run. Boston icon Carl Yastrzemski robbed Bench of his second home run. Eventually the NL prevailed, 9-3.

The game endures as the last time the stars of baseball came to Washington. The next time the national pastime’s all-star games comes to the nation’s capital is the subject of only rumor and speculation. Apparently, some in the game are lobbying against D.C. until the area around Nationals Park develops into the promised urban hotspot.

Still, the appearances of Hondo and Knowles marked one of the highlights of what still endures as the best baseball season in Washington for the past 79 years, 1969. Only the next few months will tell if a Washington team can add more sweet memories to those Frank Howard, Ted Williams, and their teammates gave Washington so long ago.

Steve Walker is the author of the book, “A Whole New Ballgame: The 1969 Washington Senators” available on Amazon: http://amzn.to/AzaNta or direct from the publisher, Pocol Press: http://bit.ly/y51taI.