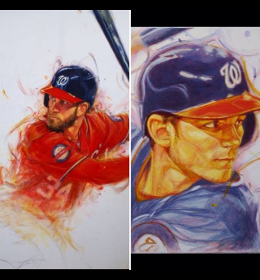

Somewhere last night, an exited kid of 10 or 11 proudly hung a Bryce Harper poster in their bedroom, and fell asleep to dream of the day when they, too, would hit a walk-off homer for the Nationals, sending the crowd into delirium.

It’s not hard to find heroes on the Nats these days. The team is off to another great start at 7-5. The past two victories came on Daniel Murphy’s walk-off double and Harper’s mad dash home Friday, and Harper’s game-winning shot on Sunday. Murphy came within one hit of the National League batting title last year, and Harper was MVP two years ago.

It’s easy to make heroes of these guys, too. With their constant exposure on TV and the internet, and a huge social media presence, it’s not hard for fans to learn what their favorite players are up to.

But it was different for the fathers and grandfathers of today’s young fans. In 1975, there was no hometown baseball team in Washington, and even if there were, not all the games would have been on TV. I poured over box the scores in the morning paper before school to find out what George Brett, Rod Carew and Carl Yastrzemski had done the night before. For stars on the West Coast, like Steve Garvey and Reggie Jackson, I had to wait for the afternoon paper to read the late box scores.

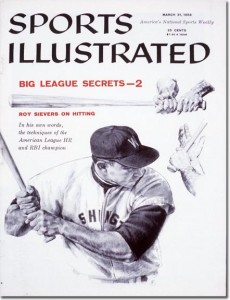

For a national perspective, we had This Week in Baseball on TV every Saturday before the Game of the Week. We also read magazines like The Sporting News, Sports Illustrated or Baseball Digest. Kids of the 50s had to be even more dedicated. There was far less television coverage, and many slept with a radio under their pillow to follow their teams.

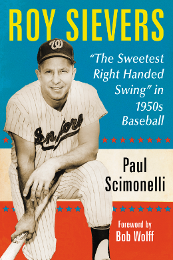

Those fans learned that Roy Sievers, who played for the old Senators from 1954-60, and expansion Senators in  1965, was a true hero. Sievers died April 3 at age 90, making this Opening Day bittersweet for Washington fans. Fans usually learned of his feats by reading the papers and listening to the radio, while some got to see him on the movie screen.

1965, was a true hero. Sievers died April 3 at age 90, making this Opening Day bittersweet for Washington fans. Fans usually learned of his feats by reading the papers and listening to the radio, while some got to see him on the movie screen.

Sievers was the star of a team that perennially finished last, or close to last, in the American League. He played in five All-Star games, including one before the hometown fans at Griffith Stadium in 1956. He hit nine walk-off home runs in his career, and 10 pinch-hit homers. He also had 10 career grand slams.

Sievers was the first American League Rookie of the Year, once the award was given in each league, with the St. Louis Browns in 1949. After surgery to repair a shoulder injury suffered early in his career, he developed one of the most feared swings in baseball, reaching even the distant 388-foot left-field fence at Griffith with great regularity. In 1957, his best season, he won two-thirds of the AL Triple Crown, with 42 home runs and 114 RBIs, beating out Hall-of-Famers Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle.

Sievers was also a movie star of sorts. In the film, Damn Yankees, he was the body double for Tab Hunter as Joe Hardy, the unknown slugger who led the Senators to the AL pennant. He wore a mirror-image No. 2 on his uniform, and the film was reversed to show the right-handed Sievers hitting left-handed. He played in the minor leagues in Hannibal, Missouri, and many fans believed that he actually was the inspiration for Hardy, nicknamed “Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo.”

Sievers lived up to his reputation as a hero, too. Stories abound of him waiting around after closing time of an autograph session to give a boy a personally autographed photo, or inviting another into the dugout at an exhibition game and having the whole team sign for him.

Kids who only heard stories about Sievers found him to be a true hero. I hope today’s stars, like Harper and Murphy, can use the abundance of exposure at their fingertips to show that they, too, are true heroes.