Every game at Nationals Park, the Nats and their fans pay tribute to members of the United States military who have recently returned from combat, some who were wounded in the line of duty. The fans seemed especially appreciative of World War II veterans in Sunday’s pregame Memorial Day Tribute, giving them a rousing welcome.

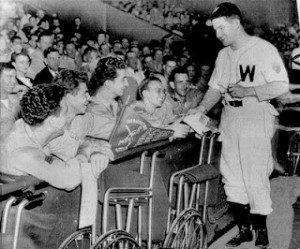

Bert Shepard

Imagine then, a Washington team where wounded service members were not only honored, but were an actual part of a ballclub that contended for a pennant. That’s what happened in 1945, when a Nationals team that few expected to do anything in the American League won 87 games and captured hearts in the region.

Americans made many sacrifices for the sake of the war effort, and while the national pastime endured, it made some sacrifices of its own. Thanks in part to an appeal from Washington owner Clark Griffith, President Franklin Roosevelt allowed the major leagues to continue playing during the war, although about three-quarters of the players, including many of the biggest stars, joined the fight in Europe and the Pacific.

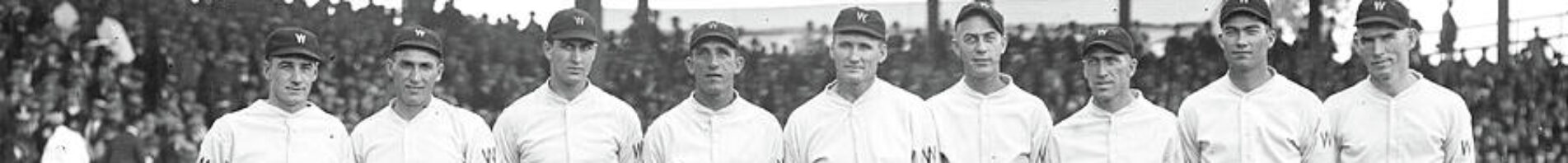

The Nats, casually known as the Senators in those days, had not contended since their last AL pennant in 1933 and were far removed from their World Series teams of 1924 and 25. Their roster, like those of most other big league teams, included aging veterans, youngsters with 4-F draft status and players returning from military service.

In fact, the only player on the 1945 team who had been with the Nats in 1933 was third baseman Cecil Travis. A three-time All Star before the war, his best season was 1941, when he hit .359, second in the AL to Ted Williams’ .406.

Travis joined the military following the attack on Pearl Harbor and spent most of the war stateside. But in 1944, he went to Europe. His service earned him a Bronze Star, but he also suffered severe frostbite in both feet in the Battle of the Bulge. He returned for the final 15 games of the 45 season, hitting .241 with a double and 10 RBIs.

Another wounded warrior on the 1945 team was pitcher Bert Shepard, who had played minor league ball before enlisting in 1943 and becoming a pilot. His plane was shot down in 1944 near Hamburg, Germany, and his right leg was wounded. It was amputated below the knee after he was he was taken as a prisoner of war.

While he was in the POW camp, Shepard taught himself how to pitch wearing a prosthesis, and he continued to practice after returning to the United States in a prisoner exchange. He earned a tryout with Washington and was hired as a coach for the 45 team.

The left-hander pitched in exhibitions and threw batting practice, but on Aug. 4, he got the call to pitch in relief against Boston. The Red Sox had clobbered the starter and one reliever for 12 runs in the fourth inning to take a 14-2 lead. Shepard delivered 5 1-3 innings of three-hit, one-run relief, striking out two, in a 15-4 loss. He later received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal between games of a doubleheader on Aug. 31.

The Nats spent the summer of 1945 in a neck-and-neck battle with the Detroit Tigers, and finished their schedule one game out of first place. But they had to wait another week to learn their fate. Griffith had the team wrap up its season a week early because he had rented his stadium to the Redskins, while the Tigers had four games remaining. On the final day of the season, they needed to win just one game of a scheduled doubleheader in St. Louis to clinch. The Nats listened on the radio as Hank Greenberg, back from military service for three months, hit a ninth-inning grand slam to lift the Tigers over the Browns in Game 1 and win the pennant.

Despite the close loss, Nats fans were captivated by the success of a 1945 team that included a pair of war heroes. They turned out on droves the following season, when the team topped the 1 million attendance mark for the first and only time before moving to Minnesota after the 1960 season.