Moe Berg is known as a man who possibly changed history, although the former Washington Senators catcher is best remembered for decidedly non-baseball skills.

Anyone who has visited the International Spy Museum has likely seen Berg’s photo and read his story, and some who have been inside CIA headquarters in Langley, Va., may have seen his baseball cards on display. Now his exploits as a secret agent who helped the Allies win World War II have been brought to life in a film that’s in limited release.

The Catcher Was a Spy is a Hollywood adaptation of the 1994 book of the same name by Nicholas Dawidoff. While the biographical drama embellishes and speculates on some aspects of Berg’s life and is not completely faithful to the book, it does depict his work for the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA. The rest of his life is just as entertaining.

Berg’s baseball abilities were summed up in a terse telegram from a Brooklyn scout to the big league club: “Good field, no hit.” It was his intellect and Princeton education that made him a popular teammate and a favorite of reporters. He was the author of “Pitchers and Catchers,” a 1941 essay in The Atlantic Monthly, considered to be a classic commentary on the game. He was also a sensation on the radio quiz show Information Please. Ultimately, his intelligence, patriotism and Jewish heritage were key in his covert service to his country.

A star shortstop and team captain in college, Berg and his second baseman would relay signals in Latin to confuse any opposing runner on second base. He became fluent in a dozen languages, and would read several newspapers each day.

After working his way to the majors with the Chicago White Sox in 1925, he prioritized law school at Columbia University over baseball, opting to finish classes before reporting for both the 1926 and ‘27 seasons. That landed him on the bench, but Berg found his true calling in baseball in 1927 when all three of the team’s catchers were injured. Berg volunteered, and in his first start, he cleanly handled a knuckleball pitcher in a victory over Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and the New York Yankees.

After that, he got permission to work his law classes around baseball and trained for the next season at a lumberjack camp, putting him in top shape. He became a starting catcher in 1928 and was known for his defensive skills for the rest of his career. He received his law degree in 1930.

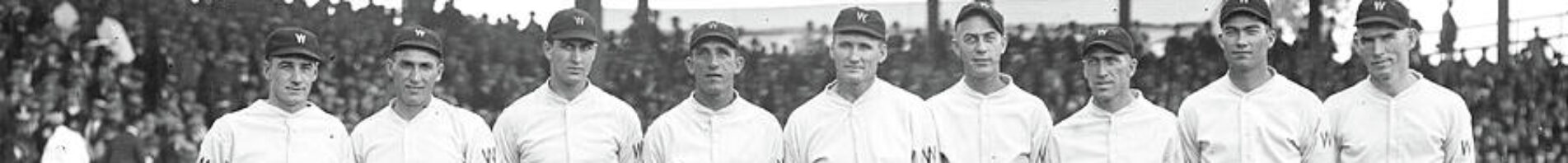

Berg played only two seasons in Washington, 1932 and ’33, but it was during his time with the Senators that he began his travels to Asia that would help his country. In 1932, Berg and other major leaguers were invited to teach baseball seminars at several Japanese universities, and afterward, he explored the country and other parts of Asia. Two years later, he returned to Japan with a touring all-star team, wrangling a last-minute invitation because of his language skills.

Being so well-read, Berg knew of Japan’s militarism and aggression in Asia. He took along a home-movie camera, and gained entrance to the tallest building in Tokyo, a hospital, under the ruse of visiting the U.S. ambassador’s daughter, who had just given birth. He snuck onto the roof and filmed the city’s skyline, harbor and munitions facilities. In 1942, he would turn that film over to the U.S. government, although according to Dawidoff’s book, the film was not reviewed until after a bombing raid on Tokyo that year .

After his baseball career, Berg began serving his country full time. Less than a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he recorded a propaganda announcement in Japanese. A little more than a year later, he went to work for the OSS, parachuting into Eastern Europe to infiltrate various anti-Nazi resistance groups, gathering information that would help the United States decide which to back.

Another assignment was to locate German physicist Werner Heisenberg, determine if Germany was close to developing an atomic bomb, and kill him if necessary. The outcome is a crucial point of the movie, so we won’t spoil it here.

After the war, Berg was to be awarded the Medal of Freedom but declined because he was not allowed to tell how he earned it. His sister accepted on his behalf after his death in 1972.

In 1958 and ’60, Berg received votes on the Hall-of-Fame ballot but was never elected. He has been inducted to the National Jewish Sports Hall of fame and is also a member of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.