Sunday’s Hall of Fame inductions made it a great day for anyone who was a baseball from the 1980s through the 2000s. Seeing the enshrinement of Vladimir Gurrero, Trevor Hoffman, Chipper Jones, Jack Morris, Jim Thome and Alan Trammel brings back decades of memories.

And while a few recent inductees, such as catcher Ivan Rodriguez and former Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, have Washington connections, it’s been quite a few years since anyone who has worn a Washington uniform for a significant length of time has joined the hallowed halls of Cooperstown.

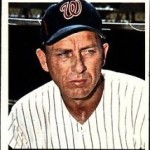

Gil Hodges

Many fans hope the man who will break that trend is Gil Hodges, who managed the Senators from 1963 through 1967. While his most noteworthy accomplishments came on the field with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, he distinguished himself as a manager with both the Senators and the New York Mets.

Hodges replaced Mickey Vernon as the Senators manager after the team traded Jimmy Piersall to the Mets for him in 1963. The Senators improved each year under his leadership, going from 56-106 and 10th place in 1963 to 76-85 and seventh place in 1967. Along the way he developed some of the expansion Senators’ most notable players, including shortstop Ed Brinkman, catcher Paul Casanova, third baseman Ken McMullen.

His biggest project was outfielder Frank Howard, who came in a 1965 trade from the Dodgers with raw, unrefined potential as a slugger. According to Mort Zachter’s biography, “Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life,” Hodges got Howard to open his stance, move closer to the plate and keep his head and hands still in the batter’s box. But most importantly, he encouraged the Capital Punisher to keep a journal on every pitcher he faced and their tendencies. As a result, Howard went from 18 home runs and 71 RBIs in 1966 to 36 homers and 89 RBIS in 1967.

Hodges was known for his even temperament and his ability to communicate with his players, even the troubled ones. One such case was Ryne Duren, a journeyman relief pitcher known for his blazing fastball, Coke-bottle spectacles, and erratic control. Duren also had a well-earned reputation as one of the hardest-drinking wild men in the game. He came to the Senators in 1965, the final year of his career, burned out, and deep in the throes of alcoholism. In his final game on Aug. 18, a hung-over Duren, mopping up in the ninth inning of an 8-2 loss to the White Sox, allowed a walk and a base hit, without retiring a batter, and was charged with two earned runs.

After Hodges removed him from the game, Zachter writes, Duren had a few drinks and drove his car to the Taft Bridge on Connecticut Avenue, high over Rock Creek Park, and threatened to jump. Police summoned Hodges, who talked him down. The team immediately released Duren, but Hodges did not reveal to the circumstances to reporters. Duren eventually quit drinking and became part of the major leagues’ alcohol awareness program in the years before his death in 2011.

Of course, baseball followers know that after Hodges was traded back to the Mets following the 67 season for Bill Denehey and $100,000 (a huge sum at the time) he went on to manage the 1969 “Miracle Mets” to an improbable National League pennant and an even more unlikely World Series victory over Baltimore.

Hodges’ supporters will tell you that his career with the Dodgers and Mets was Hall-of-Fame worthy on its own. They will note that at the time he retired in 1963, his 370 home runs were the most for an NL right hander, second most by any right-handed hitter and 11th all time. They will also tell you that from 1948-59, Hodges led all first baseman in home runs, RBIs and extra-base hits, and that the reason he won only three Gold Gloves is that they were the first three awarded for an NL first baseman, in 1957, 58 and 59. He is still widely regarded as the best first baseman of his era.

Hodges also was a key ally of Jackie Robinson, defending his teammate’s integrity after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947. His supporters will also proudly note that Hodges postponed his baseball career to serve in the Marines during World War II. He served as an anti-aircraft gunner in the battles of Tinian and Okinawa and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a Combat V for heroism under fire.

Baseball writers were not impressed with Hodges comparisons to his contemporaries, giving him a maximum of 63.4 percent of the vote in 1983, his final year of eligibility. The Veterans Committee passed him over several times, and its successor, the Golden Era committee did the same in 2012 and 2014. Its next chance is in 2020, when Hodges’ fans in Washington, New York and across the country hope he’ll finally make the cut.