By Jeff Stuart

It is not surprising that Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, who had a reputation for being hardnosed, noticed the young catcher Clint Courtney when he managed the Beaumont Roughnecks, a Yankees AA Farm Team in the Texas League in 1950.

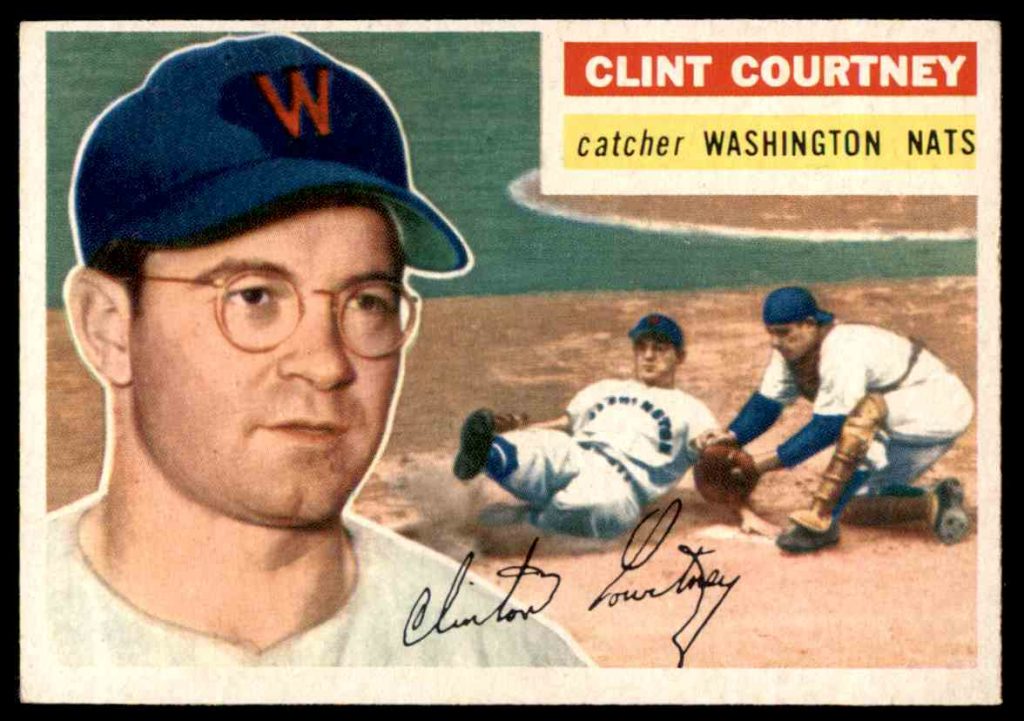

Clint Though he was an All-State Basketball player in High School, Clint was short and did not appear athletic. But he made an impression on Frank Lane, general manager of the Chicago White Sox. Who watched Beaumont beat the White Sox in an exhibition game. Lane told Hornsby, “That Courtney’s an old-time chew-tobacco type of player, like Nellie Fox and Burrhead Fain. There aren’t enough of ’em left in the majors. Too bad the little son-of-a-gun wears glasses.” “Glasses or not, Left handed or not. Courtney’ll fight his way into the Majors,” Hornsby replied. He recommended Courtney and Gil McDougland to the Yankees. “Me and Gil done tore that league apart” he said. “I think by mid-summer we had driven in about 100 runs each,” said Courtney, who made the Yankee roster along with Gil in 1951. No catcher in big league history had ever worn glasses before Clint Courtney came up. But he played little “I was trying to beat out a pretty good catcher with the Yanks. Fella named Yogi Berra,” he noted.

Courtney was named Rookie of the Year in 1952.when he was reunited with Hornsby who was then the Manager of the St. Louis Browns. He batted .286 for the Browns

Clint was frequently embroiled in fights. “He’s the meanest man I ever met, but I’m glad he’s on my side,” said teammate Satchell Paige, the pitcher, “He’s a great catcher, a kid I like to see hitting for me with the winning run on third base and one out.”

In his autobiography, Veeck as in Wreck, Bill Veeck wrote that Courtney “had served notice that he wouldn’t catch Satch. I liked Courtney because he was a rough, tough little man who played the game for all it was worth. I felt very strongly that this was a matter entirely of environment and upbringing. Once Clint got to know Satch, I was sure, he’d come around — even though I was perfectly aware that Satch would do nothing to appease him.”

Clint did catch Paige and the two ultimately became good friends. Teammate Duane Pillette and announcer Buddy Blattner nicknamed him “Scrap Iron” after a footrace against sportswriter Milton Richman in a railway yard near the end of spring training. Clint tumbled, sliced himself up all over on glass and rocks, but stayed in for the next day’s exhibition game when Hornsby threatened him with a fine. He could barely hold the bat but still got three hits against Early Wynn. According to Richman, Clint missed several weeks, but he was the Opening Day starter

A player rebellion forced Hornsby out as manager that year.

“It was force him out or kill him,” former Brown Ned Garver said of the uncommunicative Hornsby. Yet catcher Clint Courtney was not bothered by Hornsby’s style of managing. “He never spoke to me either. But I understood him. Most of these fellows couldn’t play for him but I could. He was tough but he was okay with me. But I never argued with him. I always said ‘Yes, sir” and ‘No, Sir” to him.” Browns broadcaster Dizzy Dean dubbed him “The Toy Bulldog,” and new manager Marty Marion adopted it as his pet name for the catcher.

“He hates to lose, even at hearts,” wrote Addie in May of 1954. “When an opponent slips him the black queen, his trigger temper explodes and for blocks around ladies blush. He grew up on a Louisiana Farm and doesn’t try to hide the fact that he lacks the manners and cultured speech of the college bred gentlemen that grace most of the present day big league rosters. He worked in the oil fields while completing high school and learning baseball in the sandlots. He chews tobacco and spits it out on the dugout floors. He is a pretty good ball player too. He was trained in the Yankee farm system and sold to the Browns in 52 and inherited by the Orioles in the franchise shift last September. A left-handed power hitter he is hitting .324 through the first two weeks of the season. Among his 14 hits are two doubles and one memorable home run. On opening day in Baltimore he clouted the first home run in the remodeled Memorial Stadium. The fans deluged Clint with cash and gifts totaling $1000.

He struck out just seven times in 437 plate appearances with the Orioles, which remains a club record. Throughout his big-league career, Courtney fanned only once for every 22 times he came to the plate.

On June 6, 1954 at Yankee Stadium Clint was caught using a bat with a nail in the end of it. “Ball players have been doing that for years,” said Clint. “When you’ve got a bat with good wood in it you just hate to lose it.” He said that the bat belonged to another Baltimore player and that he borrowed it because he had broken his own. Umpire Ed Hurley spotted the nail on Clint’s third trip to the plate. He had singled his first two times up. “You know, Courtney is about three times better a catcher than anyone has ever given him for being,” said Orioles manager Paul Richards. He hops around out there, but he gets the job done.” But the Orioles felt his temper and impatience to win weren’t considered conducive to the development of brilliant kid pitchers like Bob Turley and Don Larsen.

So he was traded to the White Sox at the end of the season. And on June 7, 1955, Courtney was traded to Washington for fleet footed outfielder Jim Busby. The Senators also got outfielder Johnny Groth and pitcher Bob Chakales. He batted .298 for the remainder of that season in DC, and .300 in 1956, his first full season with the Nats. That year he set career highs: games played (134), plate appearances (515), home runs (8), and RBIs (62).

On July 5, 1956, in a 10-8 win over the Orioles, Courtney, pinch hitting for Jose Valdeviolso was hit by a pitch by George Zuverink. But plate umpire Ed Hurley ruled that Clint had purposely hurled himself in front of the pitch

.He was a brief hold out in the spring of 1957 telling the Nats he was “turning around and going home” if he didn’t get his salary figure. He signed for a “slight increase” over the 17000$ he made in 56. “Man I can’t afford to stay out of baseball, I need the money – like Ted Williams -but I guess there is a big difference between his salary and mine. I might as well sign. I drove my family here from Louisiana and I have settled in my apartment.”

On May 1, 1957, Courtney, batting .357, second only to Julio Becquer’s 375, was hit on the little finger of his right hand by a foul tip off the bat of Bob Usher. He stormed off the field and got into a confrontation over lack of playing time with Manager Dressen. “I guess he was upset over his injury,” said Dressen.”I told him I was running this club and he’s catching more than anybody else. I’ve used him in spots where I Thought he’d help us. That’s a manager’s job. I slapped him with a fine. I’ve had arguments with players before and I have fined them too. But that doesn’t mean anything in baseball.”

It was the largest fine levied by Manager Chuck Dressen since he became Nats manager in 1955. But on May 7, with the Senators foundering in last place, Dressen was fired and replaced with Cookie Lavagetto.

Clint was a friend to Pedro Ramos, who said, as reported by SABR author Rory Costello “Clint Courtney was a funny guy who’d drink a lot of beer and talk about cows.” Back around 1961, it was widely believed that the fastest runner in baseball was either Mickey Mantle, center fielder for the Yankees or Pedro Ramos. Clint set up a 100 yard race between the two in Washington’s Griffith Stadium in D.C. S Courtney, knowing that Mantle was better at acceleration and that Pedro Ramos could fly after got up to full speed, secretly measured 110 yards instead of 100, to give Ramos more time to get into 5th gear. They finally raced. In the last few yards, Ramos pulled ahead and won by about a foot and a half. Mantle would have won at the 100 yard mark.

Clint had a down year in 1959. And In spring training of 1960 Manager Lavagetto wanted to see some improvement, especially defensively. “Courtney takes one step across the plate and then a full windup every time he throws to second base. I figure that with ex catchers Bob Swift, Del Wilber, Clyde McCullough and Angelo Giulani around Clint can break himself of his bad habit” who had been dissatisfied with Clint’s throwing. The Nats already had Hal Naragon and Steve Korchek as active catchers. Courtney unabashedly admitted his throwing last season was horrible.

But before the start of the season, Clint was back in Baltimore. That season, he became the first catcher to wear an oversize mitt to handle the knuckleballs of Hoyt Wilhelm. The glove was half again as large as the standard glove and 40 ounces heavier. Courtney got to break in the mitt on May 27 when Wilhelm pitched against the Yankees. As reported by Costello, The Orioles won 3-2, and the game was free of passed balls. “I don’t know how many pitches would have jumped past me with a regular glove, said Clint. ‘This was the first time I ever caught him. Boy is he rough to catch. I don’t see how anybody ever hits him.”

Courtney appeared briefly with the Kansas City Athletics in 1961 and returned for a third stint with the Orioles for the rest of the year, his last Major League season as a player.

In January 0f 1964 Clint’s wife Dorothy gave birth to their 5th child. Mrs. Courtney did not make it to the hospital. Clint had to make the delivery at home. “Nothing to it,” he said.

In an 11-season career, Courtney was a .268 hitter with 38 home runs and 313 RBI in 946 games. As a catcher, he recorded 3,556 putouts with 379 assists and only 50 errors in 3,985 chances for a .987 fielding percentage.

The son of a tenant farmer, Courtney was born in Coushatta, La., and reared in Arkansas. He did not play baseball until he was 17, and then on an Army team.

Clint died of a heart attack in Rochester, NY on June 16, 1975. He was just three months past his 48th birthday. He was there as manager of the Richmond Braves in the International League, a farm team of the Atlanta Braves.

In his obituary, sportswriter Milton Richman wrote “Clint Courtney was only tough on the outside. Inside, he was a soft, compassionate human being, more outspoken than he should’ve been at times perhaps, but with uncommon understanding and honest concern for others which always transcended the rough exterior he chose to show the world. This empathy helped him become a successful minor-league manager. Had Clint not passed away so young he might have realized his ambition of managing in the majors.

As a player, Clint wasn’t elegant, but he got the job done, especially as a field general.” “Ah can hit and Ah ain’t as bad a catcher as a lot of people think,” said Courtney himself. He threw out 41 percent of opposing runners

In July 1974 Atlanta fired Eddie Mathews as manager. The Braves narrowed their choices for successor down to two: Clint and Clyde King. The job went to King.