By Jeff Stuart

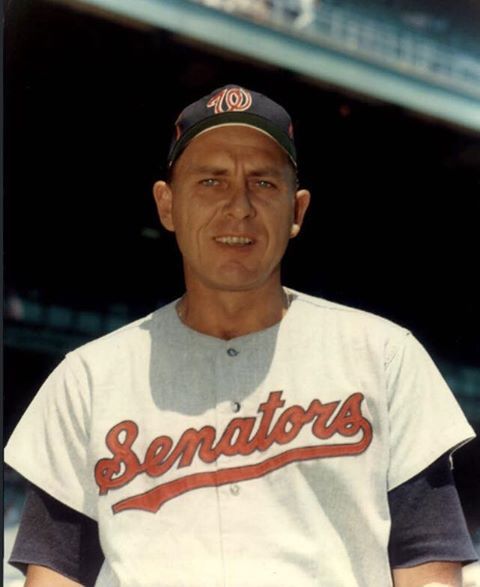

It was fifty odd years ago today Gil Hodges taught the gang to play. The legendary Dodger great Gil Hodges, acquired from the New York Mets in return for outfielder Jim Piersall, took over the helm of the Senators just 40 games into the 1963 Season. While the club lost a franchise record 106 times, Hodges proved a stabilizing influence. The club adopted the slogan, “Off The Floor in 64.” Washington did escape the cellar, finishing ninth.

The club improved every year under his patient guidance. Nobody much seemed to notice much. The improvements, like Hodges himself, were modest. In 1965 Washington obtained 6’7” outfielder Frank Howard, pitchers Pete Richert and Phil Ortega, and first baseman Dick Nen in return for Claude Osteen, infielder John Kennedy. It was the best deal in the history of the franchise. Howard, hitting mammoth homeruns, was an instant fan favorite. The team avoided 100 losses for the first time. In 1966, Senators avoided 90 losses for the first time, finishing in 8th place.

Despite losing, 8-0, to the Yankees and nemesis Mel Stottlemeyer on opening day, and some of the worst weather in a decade, the Nats set a franchise attendance record in 1967.

Hodges had helped to rework the batting stances of Ken McMullen and Frank Howard. Howard adopted a spread eagle approach and slammed 36 homers, the most homeruns he had ever hit in the majors and the most by a Senator since Killebrew hit 42 in 1959. “I would still like to see a higher batting average and fewer strike outs from him,” said Hodges. “But it’s hard to ask too much more from him.” McMullen was also urged to open up his stance. His average rose to around .260. The third baseman became the Nats most valuable player in the drive to the .500 mark in Mid August.

Hodges wanted Hank Allen to “wait on the ball.” He wanted Ed Stroud to close up his hitting stance. “He’s capable of beating out hits. But it’s difficult for him to get a good jump now the way he’s spread out at the plate,” he said.

The Nats played 18 Extra inning games. Those included a16 inning game at Chicago on April 16th, the second game of a double header, a 19 inning game on June 4th, a 22 inning game against the White Sox at RFK on June 12th, a 20 inning game at Minnesota on August 9th, and a 16 inning game against the Indians at RFK on August 17.

In the June 12th marathon, the Senators beat the Chicago White Sox 6-5 in 22 innings. The game lasted 6 hours, 38 minutes. Paul Casanova singled home the winning run at 2: 43 a.m. Afterward the American League to adopt a 1:00 curfew. In the 20 inning game at Minnesota, McMullen’s lead off homer in the top of the 20th gave the Nats the lead. Howard doubled and later scored on a sacrifice by Dick Nen to give Washington a 9-7 lead and Dave Baldwin protected it in the bottom half of the inning. It was his first major league win. The Senators lost the other three ultra-marathons.

Hodges played a 4-3 loss to the Angels in Anaheim on June 26th under protest because he felt Jack Hamilton was throwing a spitter.

The slow to rile Hodges approached umpire John Stevens a half dozen times to complain, and filed a five page report with Commissioner Joe Cronin.

“I just want justice,” he said. “90 percent of pitchers throw spitters now and then. But Mr. Hamilton displays the most flagrant use of the spitter I’ve ever seen. It’s a disgrace to baseball. It was so ridiculous it wasn’t even funny. He said he touches his visor, his mouth, his shirt, and the back of his neck to make it look like he’s throwing spitballs. I don’t think he was fooling – the way the ball was dropping. There wouldn’t have been any controversy if the umpire had merely warned the pitcher not to go to his mouth. Joe Adcock of the Indians complained against Hamilton when he pitched against his team just last week.”

In a dugout interview at Dodger Stadium a few days later, former Yankees and Mets Manager Casey Stengel told reporters, “I don’t think Hodges would have made that blast against Hamilton unless he was almost positive.”

When Hamilton pitched in Washington on July 28th the tabloid Washington Daily News bannered “A Wet Time Tonight.” advising readers to “bring your binoculars to the ball park. Hairbreath Harry is in town.”

31,101 were on hand as Ortega won his seventh straight and the Nats breezed to an 8-1 win, the Nats 15th win in their last 21 games. Umpire Ed Runge at third, plate umpire Jim Odom and Hank Soar at first took turns warning Hamilton and insisting he wipe his hand across his shirt. Senators’ hitters demanded extra looks. Hodges came out to discuss the matter in the second inning. The Nats led 3-1 when Hamilton left for a pinch hitter in the seventh.

The Nats lost the first three games and the final game in the month of July. “We found out on opening day you can’t win ‘em all,” said Hodges. But the Nats played solidly during the rest of the month, compiling the American League’s best record, 17 victories

and 6 defeats. A crowd of 23,728 watched the Nats beat the Indians on July 17th

,4-2, to complete a sweep of a 6 game homestand and stretch their longest winning streak of the year to eight games.

The usually reserved Manager admitted his teams performance had been, “Very good. We fought back to get to this stage and I’m sure we’ll continue. Howard has been going well. But so has McMullen, so has Tim Cullen, so has the pitching staff, so has everybody.”

A 2-0 win in Kansas City on August 13 moved the Nats to the .500 mark at 58-58. Cause for celebration in Washington, A crowd of 4000 greeted the team when it returned to Washington on a Sunday night. And a crowd of 27,138 watched the first game of the following homestand. The club was within 6 games of the league leading White Sox.

The Nats finished the year on a four game winning streak and there was definite enthusiasm looking forward to 1968 . The club had finished with their best attendance since 1947, finishing in 6th Place with a 76-85 record.

“Wait til next year” was more than an empty phrase.

Hodges hoped the team would hit better. He felt that lack of offense had cost the team a first division finish in 1967.

“But a great deal depends on our young pitchers to go along with Phil Ortega who has had his best year ever, and Camilo Pascual. Joe Coleman, Barry Moore, and Dick Bosman have shown flashes but aren’t outstanding yet. If they come on- well…

Epstein shows me he can lay off bad pitches and has power to all fields and rates with Paul Casanova as the best competitor on this club. Good catchers are at a premium and Casanova has done a good job, although he’s pretty tired now. I keep feeling some of the fellows we have will come on.”

Hodges was coveted by a number of teams but he had a generous expense account with the Senators which allowed him to commute to his Brooklyn home. He

felt a deep loyalty to the Senators, and had laid the foundation for success. “First division is definite possibility for us next year,” said the 43 year old manager. “This is the youngest club we’ve ever had and these fellas could all come at once next year. I expect to be here with them. I have a contract that goes through 1968 and I have every intention of honoring it. It’s nice to be wanted. But I can’t picture myself in that much demand.”

But he was. The Los Angeles Dodgers had Walt Alston but made no secret that if he retired, Hodges would be their first choice. The Mets and Pirates were both considering Hodges. Whitey Herzog was considered the front runner for the Mets job.

On November 27th 1967, the New York Mets announced the signing of Gil Hodges as their new manager. The Mets were in last place at the end of the 1967 season, exactly the same place the Senators were when Hodges arrived in Washington. Looking for the same steady improvement they had seen in their American League expansion counterpart, they turned to the popular Brooklyn hero.

The Mets sent Pitcher Bill Denehy to the Nats for Hodges, the first manager for player swap.

“I was working in the off-season at an office on Wall St. at the time,” said former Washington pitcher Jim Hannan, “I go up to New York and I tell the guys, “The Mets are going to win the pennant in a couple of years. “They said, ‘You’ve got to be out of your mind. The Mets?’

I said, ‘You wait and see. You’ve got some great young pitchers (Seaver, Koosman) and you’re getting a great, great coaching staff and a great manager’

“Gil probably knew the game from start to finish as well as any manager I’ve ever been associated with. And I’ve been associated with some great ones,” said Frank Howard.

“A manager is a great deal like a ball player, said Hodges, “He’s bound to make mistakes. The only real difference is that a manager has only one guess. You look into the mirror after something doesn’t work and you ask yourself, “would I do the same thing again?’ If you can say yes, that’s fine. When you start getting ‘no’ back from the mirror, then you’re in trouble.”

The Mets won 12 more games in 1968, escaping the cellar. But in September Hodges had a heart attack. Gil, often called the “Quiet Man”, was advised by many to “let off more steam.”

“The idea was that I should explode more often,” said Gil. “If I had done that I would be less likely to get sick. But I don’t believe it. I think that if I kept everything inside me, and didn’t tell the players when I was unhappy about something, then maybe they’d be right. But I don’t bottle things up inside me. If I have reason to be unhappy with the performance or attitude of a player, I tell him. I try to do it effectively with out blowing my top. As long as I am getting the message across, and I feel that I am, then I am not bottling things up inside myself.”

Hodges did not explode more often in 1969 but the Mets did, winning the National League pennant and taking four out of five games from the highly favored Baltimore Orioles in what is probably the biggest upset in World Series history. A glimpse, perhaps, of what might have been in Washington.