By Jeff Stuart

On June 24, 1970 two of Yankee Steve Hamilton‘s “Folly Floater” pitches retired Cleveland’s Tony Horton, a very good hitter, at the Bronx in New York to end the top of the 9th. That earned him a place in baseball history. The Yankees trailed the Indians badly and had no chance of beating starter Sam McDowell, who had his best stuff that day. Yankee starter Mel Stottlemyre did not. Nonetheless, the Crowd went crazy when the first pitch floated down over home plate and Horton fouled it off. Horton called for Steve to throw him another and the lefthander obliged. Tony fouled out to the catcher, Thurman Munson. The crowd roared and Steve raised his arms in triumph as he walked to the dugout. There is a youtube video of this event. It was far from the last time he would use the pitch and maybe not the first. Well, all lefties are considered quirky, right, and tall and lanky. Steve qualified at 6’7” and 190 pounds.

On July 7,1970, Washington’s Shirley Povich noted in his column, ”This is exactly the same blooper pitch that used to cause Yankee writer Dan Daniel and other Yankee writers to work up a pout and exclaim ‘Bush’ when Rip Sewell was throwing it for the Pirates and Bobo Newsome for the Senators. Now Yankee fans are being positively titillated by the pitch. They beg for it in the late innings when Hamilton is in there and the Yankees are either so far in front the Folly Floater can be chanced or so far behind that it doesn’t matter if Hamilton can’t get his orbiting offering over the plate. On Sunday in Yankee Stadium, the Yankees were losing to the Senators. And at that stage of the doubleheader, the faces could at least be entertained. Hamilton threw his blooper to Frank Howard. There were guffaws when Howard got a clean hit against it and was not suckered. For Yankee fans it didn’t quite make the whole day worthwhile. But it did take some of the sting from the two Yankee defeats.” The Yankees were not very good at the time. They couldn’t hit. They had starting pitchers that were more notable for swapping wives than their mound presence.

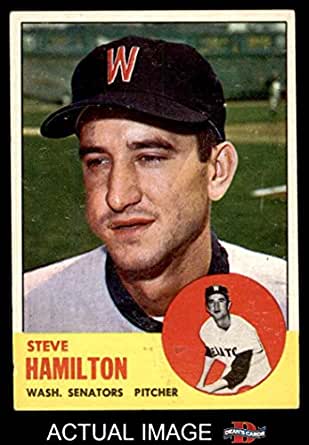

Hamilton’s career started in Washington. He had pitched 3 innings for the Indians in 1961 but that did not disqualify him from rookie status in 1962. He had been acquired from Cleveland in April for pitcher Don Rudolph and outfielder Willie Tasby. On May 31, 1962, pitching for the Senators on a Sunday in Kansas City, Hamilton lost a complete game 1-0 decision to the Athletics. With two outs in the bottom of the ninth Ed Charles hit a line drive into center field for a base hit. Joe Azcue hit a line drive into right field. Joe Hicks picked it up, and then dropped the ball. That’s a base hit and an error on Hicks. Charles came all the way around to score. That run was unearned. Heartbreak, for sure. While it earned Hamilton my undying loyalty, it did not ease the sting of the loss on a Sunday afternoon.

The winning pitcher for the A’s was Jerry Walker who improved his record to 6-2 at the time.

A win would have given the Nats a series win for the first time that year.

Hamilton was traded to the Yankees in 1963 for pitcher Jim Coates. And it was not entirely to his liking. He told George Minot of the Post, “I was secure in Washington. But when I walked into the Yankee Clubhouse for the first time and saw the likes of Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle. I thought ‘what am I doing here.’” “He did very well as a Yankee,” Wrote Minot, “winning 34 and losing 20 and being elected player representative. His blooper pitch was more than a gimmick. It actually got people out.” Hamilton pitched for 8 years with the Yankees. He also played pro basketball backing up Elgin Baylor on the Minneapolis Lakers.

He played College basketball at Morehead State Teachers College in Kentucky. “Maybe I’d still be playing basketball if I hadn’t hurt my knee,” he told the Post’s Bob Addie in April of 1963. “But the experience with the Lakers was great. I’m working for my Masters In physical education at Morehead and I teach there during the winter. When I’m through with baseball I’d like to coach both basketball and baseball.” “Steve’s freshman year with the Nats was hardly distinguished,” wrote Addie. “He had a 3-8 record. But his earned run mark of 3.79 wasn’t bad. Hamilton never steps on the foul-line when he goes out to the mound.” ”I have another habit– I don’t call it a superstition,” said the left hander. “I always pick up the ball before I pick up the resin bag. Most pitchers do it the other way around.” And he talked to himself on the mound. “I see nothing wrong with talking to myself,” he said. “It relaxes me. What do I talk about? Oh, all sorts of things. I try to make friends with the batters too. After all, Yogi Berra talks to batters. What’s the difference if a pitcher does it? The Lord gave me a voice to use and I use it.” “Called ‘Long Knife’ by his teammates,” continued Addie, “Hamilton keeps the boys relaxed in tight moments. Though only 26, he looks like a young Abe Lincoln. His dark hair, generally tousled, already is flecked with grey He affects an enormous plug of tobacco in his check and his good nature belies his serious face. He looks like he could model for Mount Rushmore right now.

But this boy can be quite a pitcher. He throws a side arm which drives left handed batters daffy. The ball comes right at a left handed hitter whose only thought is to dive for safety. Then the ball will break beautifully over the plate.” “I wish all batters were left handed,” said Steve. “I like that kind.”

He was not a star, though that Blooper pitch earned him a certain amount of notoriety. But he was pretty good. He pitched in 421 games and ended his career with a 3.05 ERA. He even started seventeen games with three complete games and one shutout.

Hamilton‘s best season was 1968 when he saved eleven games and had a sparkling 2.13 ERA and a 0.937 WHIP. But the Yankees finished last.

He finished out his playing career in 1972 with the Chicago Cubs after brief stints with the Chicago White Sox, and San Francisco Giants.

Hamilton, who also starred in track and field at Morehead State, was baseball coach there from 1976 to 1989 and athletic director from 1987 until his death on Dec. 2, 1997 of colon cancer.