Originally posted 12 years ago.

“Bob Short’s Picnic Table Diplomacy”

1969 Spring Training

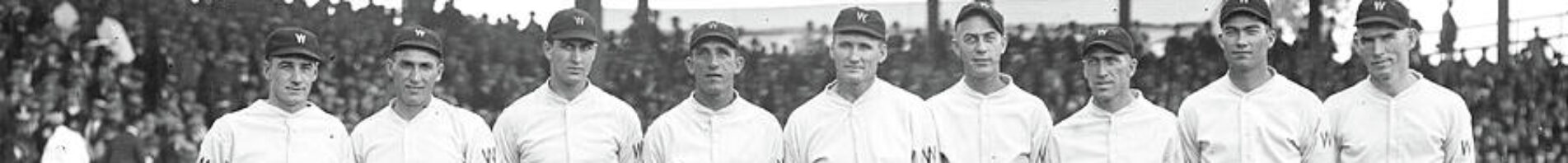

1969′s spring training may have been the most unique in Washington baseball history. Change abounded. The club sported a new owner, Robert E. Short, a celebrity manager, Ted Williams, and even new uniforms (the elegant navy blue pinstripes replaced by gleaming white home uniforms and gray road threads, with, ominously “Senators”, not “Washington”, written in script across the front).

Baseball itself experienced fundamental changes. A new commissioner, Bowie Kuhn reigned, and, in the wake of the snooze-inducing “Year of the Pitcher”, the strike zone shrunk and the pitching mound was reduced from 15 to 10 inches. In Spring Training, baseball began an odd experiment. Instead of the pitcher batting for himself, team’s could designate a “designated pinch hitter” to bat for him. Purists sneered.

New commissioner Kuhn and new Senators’ owner Short also got their first taste of the confrontational style of Marvin Miller, the head of the Major League Baseball’s Players Union. With data from Senators’ pitcher Jim Hannan, Miller succeeded in getting players to strike for more favorable pension benefits.

Most of the players and all but one of the Senators held firm to their demands. Camps opened, but most of the players stayed away. In Pompano Beach, where the Senators trained, only utility man Rich Billings showed up for camp saying, “I need this job.” In time, many players, including stars like Tom Seaver, broke ranks, but Miller succeeded in getting pension payments increased and the years required to vest reduced from five to four. Many players on the 1969 Senators — Jim French, David Baldwin, Ed Stroud, and Hank Allen to name some — received pensions due to the agreement reached in 1969.

For his part, Short recommended locking the players out and using replacements, much like the NFL did in 1987. Short was, indeed, a man ahead of his time.

The strike over and the Presidential Opener in Washington scarcely a month away, Short got to work signing his players to their 1969 contracts. In the innocent days before player agents and free agency, owners had no worries about signing their players to multi-year contracts. The reserve clause bound players for life to their teams or until they were traded or released. One-year deals were all that was necessary.

Short decided to hold his player negotiations at a picnic table behind the Senators’ batting cage. After players arrived and unpacked their belongings, they sat down across from their new owner.

Pen in one hand, cigarette in the other, Short offered his terms. He started with expected opening day starter Camilo Pascual. Washington sportswriters creeped nearby to eavesdrop. Pascual had a reputation as a tough negotiator and much drama surrounded his contract talks each spring. The reporters looked forward to seeing their favorite pitcher school the rookie owner.

As the writers settled in for the spring training theatre, the talks ended almost as soon as they began. Pascual and Short shook hands. In 20 minutes, the deal was complete, reportedly $45,000. Short spoke to the dumfounded reporters: “He said he was one of the best pitchers in the American League and I said I was one of the poorest owners.”

Other players signed quickly, falling to Short’s silver tongue. Those not in camp yet agreed to terms by phone. Catcher Paul Casanova received permission to take care of some loose ends at his home in Connecticut before negotiating his contract. Only one, the team’s best known, largest, and most talented player, held out. No upstart owner was going to tell Frank Howard what to do (more on that in Part 4).

As soon as the players signed, Williams put them to work in the batting cage. With the first spring training game just around the corner, he wanted his men well-prepared.

Ted “Finally” Gets His First Win

Part 2 of a Five Part Series on 1969 Spring Training

After the owners and players reached a deal that ended the spring strike of 1969, Senators’ players arrived in Pompano Beach to meet their new celebrity manager, Ted Williams.

Outside of Washington, where the common reaction was joy that Teddy Ballgame had joined Vince Lombardi in Washington, giving fans hope for their baseball and football franchises for the first time in years, the common reaction was that Williams would never last in Washington. Many expected the mercurial manager to bolt before the All-Star break, if not by the end of spring training.

Skeptics expected Washington’s terrible team to finish with the worst record in baseball, behind even the four expansion clubs slated to begin play in 1969 – the Seattle Pilots and Kansas City Royals in the American League and the San Diego Padres and Montreal Expos in the National. After all, the Nats were baseball’s worst team in 1968, their two best players, Camilo Pascual and Frank Howard, were also their oldest, and they would play 90 games against the AL’s top 5 teams in 1968 — Detroit, Baltimore, Boston, New York, and Cleveland — all lumped into the new East division. National sportswriters felt last place was foreordained for Washington.

Williams’ temperamental past, his outbursts, his problems dealing with the media, combined with the Senators’ futility would, many believed, drive him to distraction. Even if he held it together until September, how could he resist bolting a near-certain 100-loss team for the salmon fishing in Alaska and Canada? The thought of him inspiring the Senators to a winning season was foolish beyond comprehension. Anyone suggesting such nonsense was ridiculed.

Looking back, it seems absurd that so many people felt a man committed to helping children via the Jimmy Fund in Boston and who had served the Marines honorably in both World War II and Korea would bolt during the first year of a five-year contract. Part of the reaction may have been jealousy that a sports backwater like Washington, not New York, Chicago, or Boston, had landed baseball’s biggest name other than Joe DiMaggio, who, in 1969, served as a coach for the Oakland A’s.

The reaction also reflected the lowly place the Senators held in people’s minds (think the 2008-09 Nationals under Jim Bowden). The team was thought of as hopeless, beyond even the help of the Splendid Splinter.

The beginning of spring training games only reinforced those thoughts. The 1968 Grapefruit League Champs, the Senators’ one meager claim to fame, lost their first eight games. Game one was the worst. The New York Yankees pasted the Senators, 16-5. Despite the five runs, Williams’ charges managed only one hit — a 9th inning single by utility man Rich Billings. Pitchers from both teams struggled with the new, five inches lower mound. Walks abounded, but Teddy Ballgame’s team left the field an even bigger flop than expected.

The next seven games offered little hope. After each loss, the reporters goaded Williams, trying to get him to rip his new team of whom he had earlier said, “there is some talent here, but thinking in a baseball sense seems to be foreign to most of the Washington Senators.”

Williams didn’t bite. He said the same things managers say every spring: It’s early. These games don’t count. I’m not concerned.

Then, after the eighth consecutive loss, a sloppy, embarrassing effort against the lowly expansion Expos, Teddy Ballgame finally snapped. He yelled at a pitcher. He roared at reporters. He criticized the laziness and stupidity of his feeble, incompetent team. The pundits shook their heads knowingly. “These bums are already getting to him,” they probably thought to themselves, “there’s no way he lasts the whole season.”

The Senators’ losing binge certainly improved the negotiating leverage of holdout Frank Howard. While we will examine Hondo’s holdout later in this series, he and Bob Short did, of course, settle their impasse.

Cap Peterson Spring Training Power Display – March 15, 1969

Part 3 of a Five Part Series on 1969 Spring Training

Once the Capital Punisher arrived, Williams inserted him in the line-up as the club’s designated pinch-hitter against the Atlanta Braves. As if on cue, the Senators routed the Braves, 18-5. It was March 15, 1969 and Ted Williams had his first win as manager of the Washington Senators.

A relieved Williams said, “I’m glad to break that losing, losing, losing habit.” No one imagined the wonderful days to come for Washington Senators baseball in 1969.

Once the excitement and commotion surrounding the Senators in the winter of 1969 — Robert E. “Bob” Short purchasing the team out from under rival bidder Bob Hope, Ted Williams signing on to manage, and the players’ strike for better pension terms led by Marvin Miller — ended, the team began practicing and soon played it early slate of “exhibition games,” the term then in vogue.

Those early games became dreary affairs for the Senators. They lost again and again. Williams stewed. D.C. sportswriters nodded cynically to each other. Yet another dreadful season loomed. Frank Howard sat in Wisconsin, performing his annual spring hold-out ritual.

To make bad matters worse, the weather in Pompano Beach, where the Senators trained, grew worse by the day. Unlike other springs, where the weather was warm and sunny, with ocean breezes wafting by, the spring of 1969 was wet, cold, and incessantly windy. (Here’s a link to a current google satellite image of Pompano Beach — http://www.mapquest.com/satellite-maps/pompano-beach-fl/). It is just up the road from the famous (or infamous South Beach).

The Senators/Texas Rangers trained at Pompano Beach and played at the Municipal Stadium until 1986. The stadium stood until 2008, when the city demolished it and built a multi-field baseball complex in its place. On the link above, the baseball complex is located between NE 8th Street and NE 10th Street. Four fields, in a clover shape stand just to the west of where Municipal Stadium once stood and the heroes of Washington area children trained to play the national pastime to the nation’s capital.

This wikipedia site has some great external links with pictures of Municipal Stadium, including one with a few Senators standing near the third base foul line. Fair warning — most of the pictures were taken just before the city demolished the stadium. They are quite depressing.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pompano_Beach_Municipal_Stadium

Back in 1969, though, Municipal Stadium teemed with life and, on March 15, obscure Senators’ outfielder Cap Peterson brought the old ball yard to life with one of the best, albeit wind-aided, displays of power seen all spring.

By 1969, Peterson was a 27 year-old journeyman outfielder trying desperately to stay in the major leagues. Peterson came to the Senators on December 13, 1966 along with veteran relief pitcher Bob Priddy when Washington sent the Giants promising left-handed pitcher Mike McCormick in exchange.

The trade tilted overwhelmingly in San Francisco’s favor. McCormick won 22 games for the Giants in 1967, while Priddy went 3-7 and Peterson hit a paltry .240 with 46 RBI and 8 home runs in 122 games. In the pennant race well into August in 1967, Gil Hodges could have used some of those victories McCormick gave the Giants.

One spring day in Pompano Beach, though made all that seem in the distant past. Buoyed by the winds blowing out to leftfield, Peterson lofted three home runs. His slugging led the Senators to their first spring training victory after 8 consecutive defeats.

Ted Williams was not fooled by Peterson’s power display. With Hondo and young phenom Del Unser locks for the left and center field positions, Cap had to compete with slugger Brant Alyea and speedsters Hank Allen and Ed Stroud for the final outfield position.

By spring’s end, Peterson no longer fit in Williams’ plans. On March 31, the Senators traded Peterson to the Cleveland Indians for young minor league fireballer George Woodson. It was another bad trade for the Senators. Woodson never made the majors and Peterson turned in one of the best season of his career for Al Dark‘s Tribe.

Dark platooned the right-handed hitting Peterson, maximizing his at-bats against lefties. Peterson had a low .227 average, but he walked 24 times in 137 plate appearances for a solid .356 on-base percentage. Unfortunately, no one believed in SABRmetrics back then and 1969 ended up being the spring slugger’s last in the majors.

Peterson played three more seasons in the minor leagues, retiring in 1972 from the Minnesota Twins’ organization. For the most part, Peterson’s major league career was ordinary and is now largely forgotten. Yet, for one shining moment in Pompano Beach, itself forgotten as a once thriving springtime home for the Senators, Peterson was a star.

Hondo’s Holdout

Part 4 of a Five Part Series on 1969 Spring Training

As spring training in Pompano Beach continued, Ted Williams and his charges learned more and more about each other. Williams professed his hitting philosophy, “wait for a good pitch to hit” and being patient at the plate so walks would increase.

Teddy Ballgame also revealed to his pitchers the mental process he went through as a hitter, inside information from one of the greatest hitters of all time. He told them the pitches he looked for in each count and how he could discern a pitchers’ pattern. He also ordered them all to throw sliders, the pitch he found toughest to hit.

As the Senators attempted to put their leader’s lessons into practice, they bumbled to eight consecutive losses to open the exhibition season. Sportswriters nodded knowingly to each other, “Yep. Same old Senators. Not even the Splendid Splinter can fix ‘em.”

Yet, in addition to the void of wins, something else was missing from the Senators’ camp. A huge absence that left a massive emptiness in the team and in fans’ hearts.

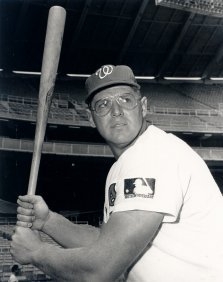

Frank Howard, the face of the franchise, the Capital Punisher, the Gentle Giant, Hondo, the only All-Star the Senators had, sat at home in Wisconsin, holding out until Bob Short met his audacious demand for a three-year, $300,000 contract. Few players in 1969 made even $20,000 and only Willie Mays, and perhaps a handful of others, had ever earned $100,000 in a single season.

Rookie owner Short fumed and sneered at the outrageous demand. Howard’s teammates and sportswriters, on the other hand, only snickered. They knew what the rube Short had failed to realize — Hondo held out virtually every year.

Howard despised spring training because he knew he would arrive overweight. Sid Hudson, the Senators’ pitching coach who doubled as the weigh-in man, said Howard usually tipped 300 pounds. Hondo knew he’d have to work like a dog to sweat off 25 pounds by Opening Day.

Hudson, now deceased, said, many years ago, “I could never get big Frank on that scale.”

Howard said, “Sidney could never get me on the scale because I was always overweight.”

So, as Hondo sat at home, presumably drinking his beloved beer and adding pounds, Short took the bait. He made numerous “best and final” offers. Howard spurned them all. He told The Washington Post in early March, “I’ll burn in hell if he expects me to call him and tell him I’ve been wrong. We’re miles apart.”

Short also refused to budge. In fact, he almost went too far in his piqued state. Unaccustomed to his charm being resisted — after all he won over even Ted Williams — Short told the press that he intended to ship the ingrate Howard elsewhere.

He claimed to have deals with the Cleveland Indians and California Angels lined up and ready to go. Depending on the day, Cleveland’s package included slugging catcher Duke Sims. More outlandish rumors said the Indians might even part with flame-throwing lefty Sam McDowell. The Angels supposedly offered Tom Egan, Roger Repoz, Billy Cowan and other similar fodder.

One can imagine Williams taking Short aside and threatening to quit on the spot if he dared trade away his best player for such ordinary lights. In any case, no deal was ever made, even though Short had said, presaging Austin Powers, when he bought the team that “I want to swing. I’m a swinger” when it came to making deals.

After a week of threats and counter-threats between Howard and Short, the Senators’ owner suddenly stopped talking about the issue. Perhaps Williams learned from his players that Hondo would eventually show up either way. Perhaps, Short, a quick study, simply figured out why no one else seemed too worked up about Howard’s absence.

He decided to wait Howard out. Eventually, one called the other and they reached a deal, reported in The Washington Post to be a 1-year deal for $70,000. Shortly after agreeing to a deal, Howard caught a flight to Florida and arrived in Pompano Beach to begin the best season of his career and the best year in the history of the expansion Washington Senators.

Short, for his part, began to wonder about that off day on the schedule between an exhibition game in New Orleans and the Presidential Opener. Why leave a day open when his Senators could barnstorm their way back to D.C. for their fun and Short’s profit? At some point during his deliberations, or perhaps even before spring training even began, Short contacted Tom Vandergriff, mayor of the city of Arlington, Texas where a dusty little minor league ballpark named Turnpike Stadium resided.

Vandergriff,who passed away on December 30, 2010, openly lobbied major league clubs to move their teams to his town.

http://bit.ly/fWAwzl — Vandergriff obituary

A much loved public figure in the Arlington/Dallas area, it is safe to assume few in the Washington, D.C. area shed any tears.

Bob Short Meets Texas Tom Vandergriff

1969 Washington Senators Spring Training: Bob Short Suddenly Books Two Games in Texas

5th of a 5 part series

Once Frank Howard signed his contract and joined his teammates in Pompano Beach, the Washington Senators felt whole again. The club won their first game with Hondo in the line-up as the “designated pinch hitter.”

Washington won seven of their last 16 games in Florida to finish that portion of their schedule with an 8-17 record. Needless to say, they did not retain their 1968 Grapefruit League crown, though that dubious honor mattered little once the real games began.

The Senators looked forward to the end of the long and uncharacteristically cold and windy spring, with the Presidential Opener a mere three days away. They would return home to D.C. after an already planned side trip to New Orleans for two exhibition games against Roberto Clemente and the Pittsburgh Pirates. While tired, New Orleans seemed not a bad place for a bunch of bored young men to spend a spring evening and play some baseball.

Except new owner Bob Short threw his employees a curveball. After some Spring rains in the New Orleans area, Short dispatched his Head Groundskeeper, Joe Mooney, to inspect the site of the games scheduled for April 5 and 6, the Louisiana State Fairgrounds. While the locals disagreed, Mooney declared the field unfit for use, whether under instruction from Short or not has never been determined.

Short then claimed he had tried in vain to reschedule the contests in Milwaukee or Richmond, but neither city had their baseball stadiums ready to host major league visitors. All of a sudden, Short claimed, he found a venue thanks to the good graces of Tom Vandergriff, Mayor of the tiny city of Arlington, Texas, situated between Dallas and Fort Worth. Apparently, Vandergriff, who had been attempting to lure a major league team to his little town of 20,000 people since 1958, guaranteed Short two sellouts in tiny 15,000 seat Turnpike Stadium.

Even in April, Turnpike was hot, dusty, and far below major league standards. With travel plans changing on Short’s whim, the team arrived in Texas worn out and unmotivated. The Pirates, a similarly weary but much more talented club, crushed the listless Senators in both games.

Vandergriff severely oversold his city’s ability to turn out for the games. While he promised Short 30,000 fans, only 9,000 attended, barely enough to cover the teams’ plane fare.

To boot, Ted Williams had an exhausted team on his hands that had to fly from Arlington, Texas to Friendship Airport in Baltimore the evening before a day full of Opening Day festivities, including President Richard M. Nixon throwing three “first pitches” into the waiting arms of Senators and New York Yankees.

It is difficult to determine when Short and Vandergriff made their deal to play the two games in Arlington, Texas, but it strains credibility to think plans came together at the last minute. Perhaps Short arranged these exhibitions shortly after or even before purchasing the Senators.

This much is known — Bob Short knew Vandergriff coveted a major league baseball team. He also knew the Senators’ lease for use of RFK Stadium expired on September 29, 1971. He knew baseball had named a rookie commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, who was widely viewed as weak and unable to impose his will on the owners. It is entirely plausible that Short and Vandergriff made, or added details to, their plans to move the Senators to Texas after the 1971 season.

The Senators returned to Arlington for exhibition games in 1971. By then, most folks knew Short and Vandergriff intended to move the national pastime from the nation’s capital to a small suburb in the shadow of Dallas. Less than six months later, the deal was done.

But in 1969, the two Texas exhibition games merely delayed the start of a magical, unforgettable season that saw the Senators win 86 games. No Washington baseball team since has come anywhere close to that win total.

Two short seasons later, baseball in Washington was gone and fans endured 33 years of silence and waiting.

To add insult to injury, Vandergriff’s grandson, Parker, is hard at work lining up actors (including Mark Nutter who appeared in the first season of Friday Night Lights) for a movie version of his grandfather and Bob Short’s hijacking of the nation’s capital’s baseball team. The working title, an unintentionally ironic “Legends of the Game.” http://bit.ly/zSIY6B

Here is a link to a photo of Vandergriff and Short at the first game in Arlington, Texas in 1972: