By Jeff Stuart

At the time of Joe Cambria’s passing on September 24, 1962 at the age of 72, Washington Post Sports columnist Bob Addie called him. “the best baseball scout that ever lived.” At a birthday party for the late Clark Griffith some years earlier, Cambria told Addie, “I’ve been with this club so long. I have only one wish when I die: I want to be buried in the uniform of the Washington Senators.”

About a month before his death, Joe, then with the Twins, reiterated, “I haven’t changed my mind. I still want to go out in a Washington uniform. Washington was “Mr. Griffith’s Club.” Clark Griffith died in 1955, and Calvin Griffith had moved the team to Minnesota in 1960.

Cambria was best known for being the first scout to search Latin America. Cambria owned numerous minor league teams and many Cuban players would sign for less because they were convinced that Cambria was the man who could take them north.

During the “Wrecking Crew” pennant run in 1933, the Senators lost money. The costs of acquiring players exceeded the profits. In 1933, Cambria, an Italian-born laundryman, bought the Chicago Cubs’ Albany franchise – players and all – for just $7,500. Griffith had.” paid $150,000 for the Chattanooga franchise a few years earlier, so he took note of Cambria.,

In 1934, Griffith finally met Cambria. Both were scouting talent from the teams fielded by the Huerich Brewery in Washington. Joe had also bought a team in Hagerstown, Maryland and had run into financial difficulty. “I didn’t have enough money to meet my payroll,” said Cambria. “After pleading my case with Mr. Griffith, he wrote me a check for $1.00.” The two men developed a close working relationship. As a result, acquisition costs dropped to about $100,000 in 1936, and by 1944 had dropped to $9,500. During the World War II years Cambria’s Cubans helped to revive club. Cubans were exempt from the military draft in the United States. And yet the SenaIors remained competitive, placing second in the American League in 1943 and 1945.

“That old trafficker in baseball flesh,” wrote Shirley Povich in 1938, “the little round man known as Joe Cambria, watched George Case skim across a good 50 yards of outfield terrain to haul down a fly ball and then muttered, ‘I think he’ll do it.” Povich continued, “That’s the way Cambria works. No written pact exists. He presents, for Griffith’s approval, the refined products of his minor league baseball factory. If they meet the test of the big leagues, he is paid off handsomely. Joe avoids the beaten paths of baseball scouts. He doesn’t trifle with the big shot minor league stars because they would cost money and the Washington club doesn’t have that kind of money to spend. He snoops around the back lots and the high schools and around the back lots and the high schools and the Latin American outposts where players, can be signed for the equivalent of a song. It- is because of Cambria that the Nats are able to operate without a single talent scout.”

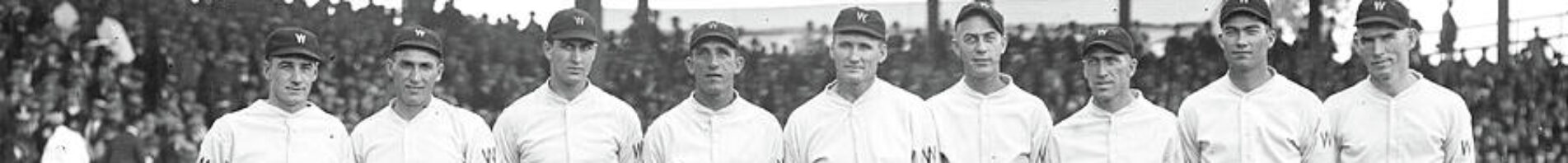

Prior to 1938, Joe Engel, former Nats pitcher and roommate of Walter Johnson, scouted for the Nats and did not do badly. He discovered Goose Goslin, Joe Cronin, Alvin Crowder, Bump Hadley, Cecil Travis, Ossie Bluege, Bucky Harris and Doc Prothro.

“Griffith would tell Cambria, ‘We need a shortstop. Get me one.’ Papa Joe would always come up with one,” wrote Bob Addie. Cambria’s manipulations with players and franchises finally got him in dutch with Commissioner Judge Landis. He was called on the carpet a half dozen times. But because he was giving Griffith first option on his talent, the Washington owner, a great and good friend of Landis, got him off with small fines. Eventually Landis commanded Cambria to give up his ball clubs and work for Griffith as a scout, exclusively, if he wanted to stay in base-ball. Cambria compromised by giving up his ballclubs and working for Griffith as a scout. League. He hasn’t done badly. For Griffith it is one of those beautiful friendships.”

Though known for his work in Latin America, Cambria presented other talent to the Senators as well, including Case, Mickey Vernon, Early Wynn, Ed Yost and Walt Masterson. Others were willing to pay $10,000 for the speedy Case but Cambria sold him to Griffith for $1,000.

“I had a verbal agreement with the Browns after working- out with them in Philadelphia,” said Vernon. “They agreed to a 400-dollar bonus. Doc Jacobs, my coach at Villanova had the Easton club in the Eastern Shore League, where I got my start. St. Louis had a working agreement with Easton but cancelled it after deciding there weren’t any good prospects on the team.”

Cambria latched onto Vernon after the Browns snubbed him, offering him a contract for $500. The Phillies offered double that amount but they were a day too late.

Cambria once stated, “You could pay more for a hat than I paid for Vernon, Yost, Case and Masterson. And I never gave anybody a nickel bonus. I don’t believe in making a boy a financial success before he starts.” Cambria signed most players for his clubs and the Senators out of high school, sometimes for the price of a meal or an ice cream cone. Cambria lived frugally. He was extremely loyal to Griffith, turning down significantly higher offers for Vernon and Case, among others, and sending them to the Senators.

Cambria owned an apartment building and several saloons in Havana. One small restaurant Was attached to Gran Stadium, set behind the center field scoreboard. He co-owned the Havana Cubans of the Florida International League. The man who represented the Washington Senators was an important figure in Cuba. He was a personal friend of President Fulgenio Batista and later forged an even stronger bond with Fidel Castro. Castro was once a pitcher in Cuba.

“I still got a card on him,” he told Morrie Siegel. “I scouted him when he was pitching for the University of Havana. I said then, ‘fair fastball, good control, no curveball. Strictly Class F material.” One of the first Cubans to sign with the Senators was Connie Marrero, the oldest living former major leaguer. “The little guy with the fire hydrant physique is not only the life of the Nats’ party,” wrote Siegel in March, 1951,” but the lifeline of the pitching staff as well. His infectious personality and baseball savvy haven’t yet transformed the club into a pennant threat or even rid his teammates of their dead fish personality. But he’s in there pitching on both counts. The ageless little runt with the big curve has already scored nine successes, more than one fourth of the games the Nats have won this season. ‘Me old enough but not yet too old,’ said the ebullient Marrero, who was 40 at the time. ‘Manana we ween, don’t worry too much,’ he would encourage his teammates. Once a fan offered him a cigar if he’d autograph a program. “It take two of these kind ceegar for me to sign for you,” quipped Marrero.

Former Washington first baseman Julio Becquer, signed in 1951, recalled, “We don’t call him ‘Joe Cambria,’ we call him ‘Papa Joe,’ because he really, to most of us, he was like a father: If we have any problems, well, we go to Papa Joe. He was a short guy, kind of stocky, smile on his face all the time, and he is just a great human being.”

Camilo Pascual cost Papa Joe $175. “You should see Pascual who is pitching for Cienfuegos in the Cuban League,” reported Cambria to the Nats. “He has an 8-4 record and the other day pitched a 14-inningshutout in which he struck out 15 men. In fact, he has 103 strikeouts for his 12 games down here. He seems to have picked up a lot of savvy. He is working his changeup better and has a better fastball than ever. Of

course, he throws about the best overhand curveball in the big leagues. But he’s developed a sidearm curve now. That really should bother the right-handed batters in the American League next season.” Pascual turned down a $4,000 offer from the Dodgers to sign with Washington.

“He was an indefatigable worker, completely dedicated to ‘Mr. Griffin,’ as he called the longtime Washington owner,” wrote Addie. “Papa Joe cared little for his own comfort. For most of his years he affected baggy pants and that full length shirt with fake pearl buttons on them, so popular with the Cubans. He once handed in an expense account listing 14 cents for breakfast. He probably handed in the most frugal expense accounts it was ever Griff’s to approve.”

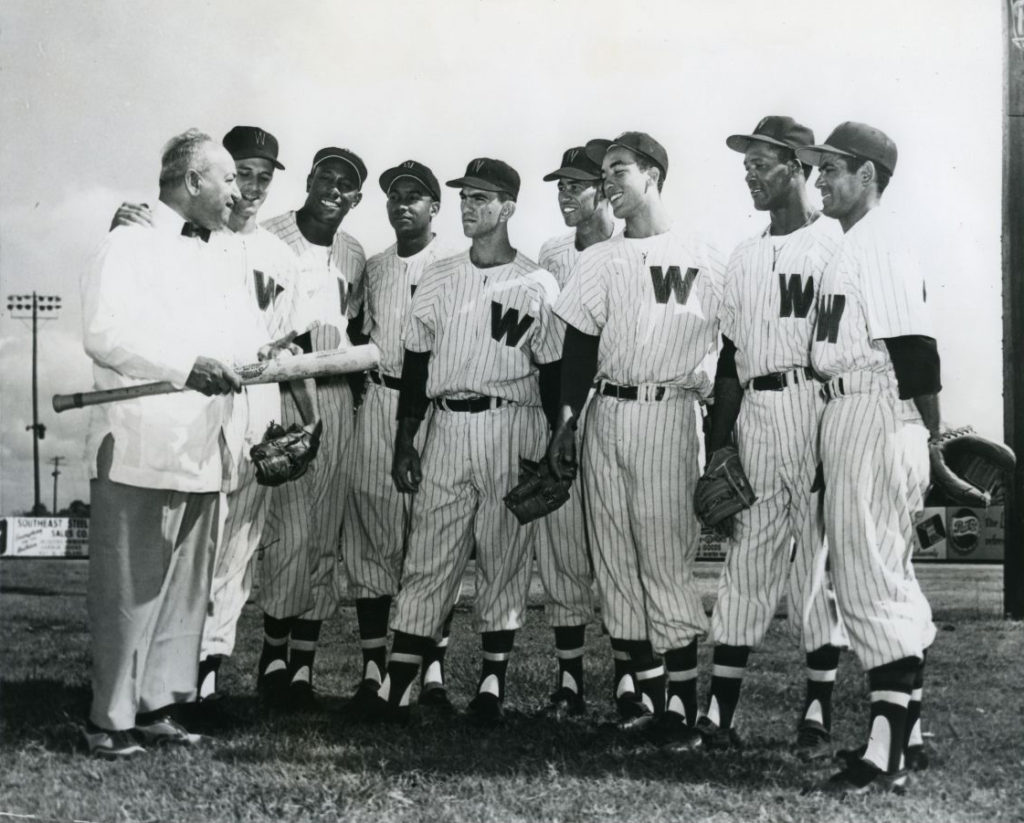

Cambria scouted and signed nearly 400 Cubans to organized ball, including pitchers Marrero, Pascual, Pedro Ramos, Mike Fornieles, Sandy Consegra, and infielder Jose Valdivielso, Zoilo Versalles, Bobby Estallela, Willie Miranda and Becquer, and outfielders Carlos Paula and Tony Oliva. To keep the young Cubans from getting homesick he would take them to Spanish restaurants. He bought Miranda Rhumba records.

If you go into his office you would always see seven or eight or ten players around him all the time,” said Becquer.” He helped many, many, many players.”

L-R Joe Cambria, Pedro Ramos, Carlos Paula, Julio Becquer, Camilo Pascual, Hill Hooker, Jose Valdivielso, Webbo Clark and Yoyo Davalillo