By Jeff Stuart

In the summer of 1957, my mother – who did not like baseball – came home from a Senators promotional event one day with a baseball autographed by Roy Sievers. My brother Chris and I almost immediately took the ball outside and played with it.I have no idea how many hours of entertainment we got from using that ball. But the autograph was soon obliterated. Both my brother and I can now honestly say that we regret not putting the ball in a safe place. Because it was an autograph worth keeping.

When Sievers joined the Senators in 1954, he quickly became a favorite of then Vice President Richard Nixon. “Roy Sievers is a boy who symbolizes great character, sportsmanship and guts,” said Nixon, who would meet with Roy on occasion to discuss baseball.

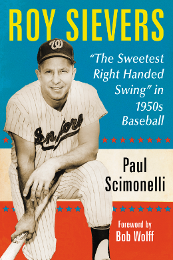

Casey Stengel once said that Sievers was “the sweetest right-handed swinger in the league.” But a serious arm injury almost prevented baseball fans from ever noticing that swing And only a gamble by Brown’s owner Bill Veeck and another chance taken by Washington’s Clark Griffith kept his career from being cut off almost before it began.

Sievers was a St. Louis native who grew up only a few blocks from Sportsman’s Park. That was where he acquired the nickname “Squirrel.” “When you’re in high school at that age, you’re a little goofy anyway,” Sievers laughed. “I played basketball, baseball, and ran a little track. In basketball one day, a kid said, ‘You know what? You’re really squirrelly, you know that?!’ From that day on, that was my nickname. It just stuck to me.” Surprisingly, despite a good deal of teasing, he liked the nickname, and even had it engraved on his signature Louisville Slugger bats.

The Cardinals were interested in him, but Roy was signed by the Browns on October 14, 1944. His signing bonus was a new pair of baseball spikes. Because he was still in high school so his Dad signed for him. Jack Fournier of the Browns waited until that date so that Sievers could play out his American Legion eligibility, which had ended in September.

The start of his professional career would have to wait, however. After graduating from High School he was drafted into the Army, serving at Camp Fannin, TX and also Ft. Knox, KY. He played service baseball until February 1947.

In Later that year, Roy enjoyed his best season in the minors. He had 159 hits, 121 runs, 21 doubles, 5 triples,34 home runs, 141 RBI and 8 stolen bases at n 125 games with Hannibal of the Central Association. He played with Springfield in the Three-I League and Elmira in the Eastern League in 1948. He led Three-I League outfielders in assists (22) in 1948 and showed great promise defensively as an outfielder.

Sievers was 22 years old when he broke into the big leagues on April 21, 1949, with the St. Louis Browns. On May 14, Sievers gave an early hint of things to come. He had a double and home run to drive in four runs in the Browns 8–3 win over the Detroit Tigers. He became the first American League Rookie of the Year that year, batting .306, hitting 16 home runs, and driving in 75 runs.

However, he hit a serious rough patch, batting just .238 the following season. He was farmed out to San Antonio in the Texas League. Browns coaches tried to get him to hit more to right field; the result was a terrible sophomore season. “I said I was going back to my own way of hitting and I never let anyone change me again,” said Sievers. But the slump was the least of his problems. It was in San Antonio that he dislocated his shoulder trying to make a diving catch. Limited to 31 games in 1951, he hurt himself again the following spring, dislocating his right arm during infield practice at spring training in 1952. He played in only 11 games. Though his future looked bleak, Browns owner Bill Veeck gambled that Sievers could come back.Veeck, with a wooden leg, hit grounders to him so that that Roy could work on his throwing. Finally, Veeck sent him to Dr. George Bennett of Johns Hopkins Hospital for surgery. The result was a minor medical miracle. Sievers was able to play 92 games in 1953.

“He was probably one of the best owners I ever played for.” Sievers said of Veeck. “He did a lot for the ballplayers and he did a lot for the fans. If you got a winning hit against a top, first-division ball club, at the end of the game when you’re going through your locker, why, there’d be a check for $250 or $500 for you to buy a suit or a nice coat or whatever you wanted. He was just a super man.”

On February 18, 1954, the Washington Senators gambled also, getting Sievers from the Orioles in exchange for outfielder Gil Coan. Sievers was only the third choice in Washington’s plans. They first offered Coan to the Orioles in exchange for Johnny Groth. But the Orioles had already traded Groth to the White Sox for Sam Mele. Griffith then offered the Orioles Coan for Mele. He ultimately settled for Sievers. The White Sox passed on Sievers at the time, because his doctor had told them that the first long throw he had to make might be his last.

“Well, knock on wood… it turned out to be the best deal of my career,” said Sievers. “Because I went to Washington and ended up breaking their home run record four years straight. I was very happy about that. It was a blessing in disguise.”

When he came to Washington, Sievers himself informed Manager Bucky Harris, “The doctors told me I can’t play the outfield. That’s why the Browns had me playing first base. I can’t throw anybody out from the outfield.” The injury reduced him to throwing with a side-armed delivery. Nevertheless Harris told reporters, “We’ll keep him.The way he hits he’ll be a valuable man to have around.” Sievers performed for Washington for 6 productive seasons from 1954 to 1959. In 1954 he set a franchise record hitting 24 homers. He drove in 100 or more runs and played in at least 144 games each year from 1954 through 1958.

In 1957, despite playing for a last place club, Sievers led the AL with 42 home runs and became the first Senator to win the RBI crown (114) since Goose Goslin in 1924 and the first Senator ever to win a homerun title. Roy placed third in the MVP ballotting with 205 points. Mickey Mantle, the winner, had 233, and Ted Williams ,209. “Ted, you deprived me of my triple crown”, he told Williams. Sievers pointed out that he had led the league in home runs and RBI , and that Ted had beaten him out for the batting title by a mere 87 points, .388 to .301.

Sievers belted home runs in six straight games that year, tying an American League mark held by Ken Williams and Lou Gehrig. The major league record is eight, set by Dale Long in the National League (1956), and matched in the AL by Don Mattingly (1987) and Ken Griffey, Jr. (1993). That streak ended on August 4. Washington defeated the Detroit Tigers 4-3 that day, as Sievers hit his 30th homer of the year.

Sievers appeared as the “swinging double” for actor Tab Hunter, as Joe Hardy, in distance shots in the 1958 movie Damn Yankees. Hardy was left-handed. So the right-handed hitter was outfitted with a mirror-image Nats uniform and the film was reversed in production.

A “murderer’s row” of sorts, Roy Sievers, Bobby Allison, Jim Lemon, and Harmon Killebrew captivated Washington fans during the 1959 season. The media adopted the acronymn “SALK” to refer to the sluggers, a play on the Salk Polio vaccine developed by Dr, Jonas Salk. The quartet did not disappoint. The team was second in the league in homeruns. Allison hit 30. Killebrew hit 42. Lemon hit 33, and Sievers hit 21.

On April 4, 1960 Roy was traded to the White Sox, the team that had passed on him in 1954. Chicago wascoming off a World Series appearance in 1959,and the team was badly in need of offense, Consequently the Sox sent Earl Battey, Don Mincher and $150,000 to Washington. For Chicago, acquiring Sievers was no gamble. Roy performed well for the White Sox in two seasons in Chicago, batting .295 each year. He hit 28 homers his first year, driving in 93 runs and 27 homers the second, driving in 92, He lead the team in homers in 1960. Only Minnie Minoso had more RBI’s. The second year Al Smith had one more homer and one more RBI. His 21-game hitting streak in 1960 was the longest for any player that season.

On November 28, 1961 he was traded by the White Sox to the Philadelphia Phillies for Charley Smith and John Buzhardt. He played for the Phillies from 1962 to 1964 and remained productive. In 1963 he matched former Philadelphia A’s great Jimmie Foxx , Glenallen Hill, and Kurt Bevacqua. as the only players to pinch hit grand slams in both the AL and NL. On July 19, 1963, with one out and a man on in the ninth, he hit his 300th career home run off Roger Craig to give the Phils a 2–1 win over the New York Mets.

The Phillies were in a pennant race in 1964. But, in July, Philadelphia sold Sievers to the expansion Senators. He hit just .180 for the year. After leading the NL by 6 ½ games with 12 to play, the Phillies collapsed and the Cardinals won the pennant. “It would have been super to play in the World Series,” said Sievers. “I thought for sure Philadelphia was going. But, I pulled a calf muscle. Then, GM John Quinn decided to get rid of me because I was getting up in age. That‘s how things go in baseball.”

He played his final MLB game on May 9, 1965, at RFK Stadium (Then DC Stadium) ending his baseball playing career at age 38.

Sievers coached for the Cincinnati Reds in 1966. He then managed in the Mets’ system for two years with Williamsport of the Eastern League and Memphis inthe Texas League. He later piloted the Oakland Athletics Burlington team ofthe Midwest League, ending his professional career at age 43.

After leaving baseball, he worked for the Yellow Freight Company in St. Louis until retiring in 1986. Later Sievers played in several old-timers games, clad in a replica St. Louis Browns uniform. He received many offers to buy that uniform, which was a gift from St. Louis Cardinals General Manager, Bing Devine.

The four time All-Star had ten walkoff homeruns during his career. Only Babe Ruth (12); Jimmie Foxx (12); Stan Musial (12; Mickey Mantle (12); Frank Robinson (12); and Tony Perez (11) had more.

His lifetime total of 318 homeruns would undoubtedly have been higher had he not played for six years during the prime of his career in cavernous Griffith Stadium.

In 1996, Sievers was enshrined in the “Circle of Fame” honoring Washington Sports heroes at RFK Stadium.

Roy celebrated his 79th birthday in 2005. Forty years after his last game in the majors, Sievers returned to the place where he had played his final game for the opening of a new baseball era in DC baseball. On April 14, 2005, Opening Night for the Washington Nationals, Sievers, appropriately, took part in the pre game festivities where former players handed off the ball to a new generation of Washington players. He thinks baseball will work this time around in the nation’s capital. “I’m glad Washington got it back because they deserve it,”said Sievers.

“Opening Day was just a super atmosphere. They drew 30,000 to 35,000 people every night that year. It was a great thing for Washington and I just hope they stay there.”