By Jeff Stuart

June 2006

“Walking man, walking man walks

Well, any other man stops and talks

But the walking man walks”

On my 10th birthday in the summer of 1955 my Dad took me to Griffith Stadium in Washington to watch the Senators play a Sunday doubleheader against the Baltimore Orioles. It was my first trip to a big league baseball game. But I had followed the Senators on radio and TV and in the Newspapers.

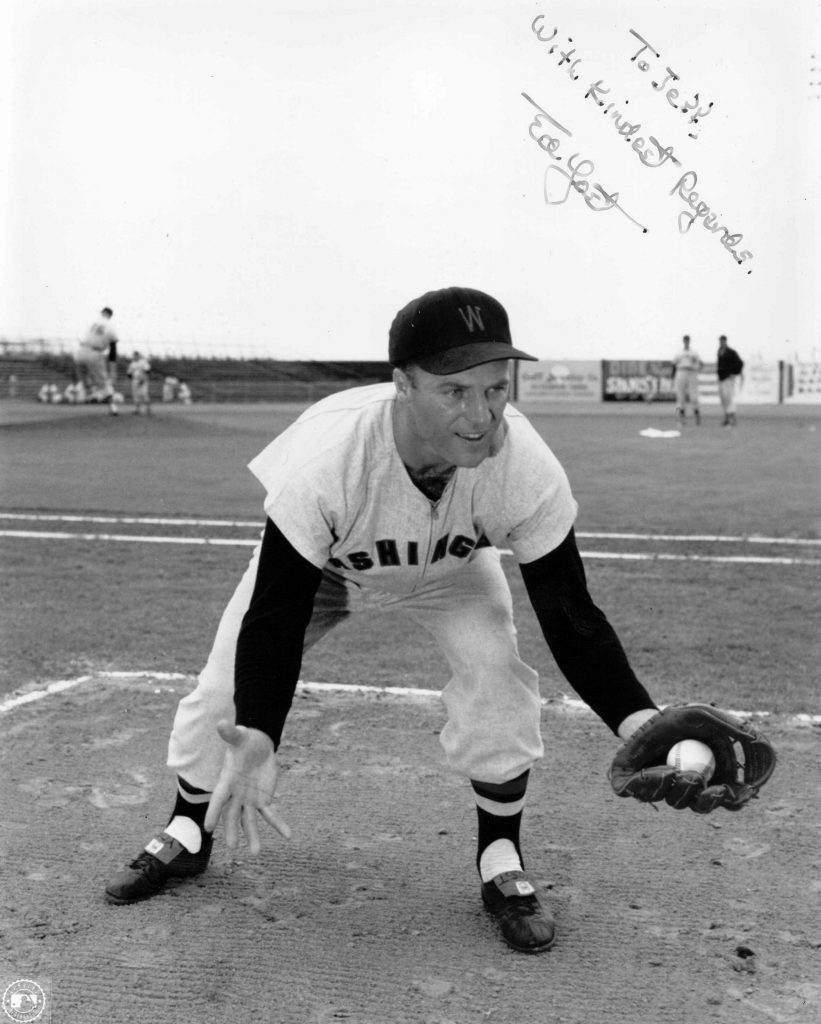

My Dad brought upper deck tickets along the third base line. We walked along the rickety ramp to the upper grandstand. It was my first view of a grand old ball park. Bob Costas and many others have mentioned the magic of that moment and the greenness of the grass. I noticed all that. I noticed the smell of baking bread. But mostly I remember looking down and seeing Eddie Yost, in home whites, taking grounders at third base. He was already my favorite player. My Dad knew that. But from that moment I bonded with him like a baby chick does on his mother.

Yost was a ten year veteran by then. He made his major league debut on August 16, 1944, a year before I was born. The Boston Red Sox invited Yost to work out with the team in Boston in 1943. They liked what they saw. But when the Sox sent a scout to his Brooklyn home to sign him, they learned, from his mother, that Eddie was in St. Louis with the Washington club. Yost signed with Washington before the 1944 season. Boston Manager and former Nats shortstop Joe Cronin told Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich at the time, “Any right handed hitter who would sign with Washington when he had a chance to shoot for our left field fence deserves no sympathy.” But the Nats had finished 2nd in 1943. Boston finished 7th.

Anyway, the Nats got him dirt cheap. The bonus he got from famous scout Joe Cambria was only $500. He was only 17 then. He was fresh from New York University and the Bushwick semipro team of Brooklyn. He never played a day in the minors. But he might have. Yost went 1 for 3 in his Major League debut at Griffith Stadium, getting a solid single to left his second time up. He handled three chances in the field flawlessly. The Nats lost to the White Sox, 7-2. However, in 14 at bats for Washington in 1944 he batted just .143 and walked only once. He clearly needed seasoning. But a war intervened. Yost spent two years in the in the Coast Guard. He was discharged in 1946 and asked Griffith to send him to the minors. He even pleaded his own case with Baseball Commissioner Chandler. But under the GI Bill of Rights, all those who had fought for their country couldn’t be demoted or fired from their jobs for at least a year. Yost had joined the Coast Guard as a major league.

So he remained with the Nats. When he opened the season at third base against the Yankees, the Yankees tested him immediately by bunting repeatedly. Yost threw them out. They stopped bunting. With veteran Cecil Travis slumping and hurt, Yost got more time at third. Saddled with the lead off spot, he hit .277 for the first two months of the season. He was a legitimate Rookie of The Year candidate. And he was already drawing walks. (He walked 45 times in 1947) He impressed Manager Ossie Bluege, an old third baseman himself, with his defense.

“Yost hasn’t done anything wrong yet,” he said, “except lay back too far on one bunt by Hal Peck of the Indians and that was as much my fault as hit. I should have moved him in, but he’ll learn those things for himself, I’m sure. He does everything else well, and I haven’t seen him flinch yet on the hardest kind of a ground ball. I’d say he’s in the big leagues to stay a long time.”

Yost had better than average speed. “Yost would be a good base runner if he knew how to cheat,” said owner Clark Griffith. “He doesn’t know how to steal a lead on a pitcher.” Yost would go on to steal 72 career bases.

Eddie Yost was born October 13, 1926 in Brooklyn, New York City. Not a Hall of Fame candidate, he was, nonetheless a very productive player. At 5’10” and 170 pounds, batting and throwing right handed, he became the Senators’ regular third baseman and lead-off hitter. A constant presence in the Nats lineup for a decade, he was Washington’s ironman, their Cal Ripken, playing in 838 consecutive games from 1949 to 1955. It was the eighth longest streak in major league history. He wore uniform number 1 from 1951 on with the Nats, appropriate for a lead off hitter. He wore numbers, 6 in 1944, 28 in 1946-47, 7 in 1948-49, and 45 in 1950.

YOST STATS

Nicknamed “the Walking Man”, he drew 1,614 bases on balls during his 18 years as a major league player, leading the American League six times. In 1956 Yost had 151 walks and only 119 hits, becoming one of only seven major leaguers to record more walks in a season than hits.

Only nine players in all of baseball’s history walked more times through 2005. Every year from 1946-1960 the AL leader in walks was Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle or Eddie Yost.

Yost’s life-time batting average, through 2,109 big league games, was only .254 but his on-base-pct, .395 ranks with baseball’s finest hitters. Nine times Yost had an on-base-pct over .400 topping out at .440 in 1950. He hit 139 home runs. . In 1959, Yost hit six lead-off homers and ranks 4th in history in lead-off home runs with 28. He also hit 337 doubles, 56 triples, and scored 1215 career runs.

Regarded as the best fielding 3rd baseman of his time, Yost led all major league third baseman in putouts a record 8 times and his carrier total ranks third all-time.

When he retired in 1962, he had played a major league record 2,008 games at third base, and held AL records for putouts, assists, and chances at third.

EDDIE ON WALKS

Why did Yost draw so many walks? Perhaps he explained it best in own words in a 1953 interview with Shirley Povich.

“Sure. I’ve been reading that the fans are squawking that I’m base-on-balls crazy. They say I’d hit more if I didn’t wait so much. I don’t care if I hit .133; I am not going to swing at bad pitches. Those pitchers are not walking me because they feel friendly toward me. The opposite is more true. They’re careful not to lay one up there for me. They pitch to me like a .400 hitter. They may be flattering me, but the fact remains they show me a lot of respect. I admit it may be too much. I am not out for those bases on balls. I’d rather be in there getting those hits. That’s what counts most when you start talking contract. But I’ll take the walk if I can get it when it looks as if it will do the club some good; especially if I’m leading off an inning, or if it helps move a runner up. If I do say so myself, I can look ’em over pretty good. I might have hit more if I didn’t go for some of those walks. There were pitches that were good enough to hit, perhaps, but there were times, too, when a walk was as good as a hit and I couldn’t go for the blows. I took some pretty good strikes, waiting ’em out some times. If I had been base-hit-crazy, I’d have finished with a better average, perhaps, but I wouldn’t have been playing the percentages for the good of the team.”

Former White Sox Manager Paul Richards did not want his pitchers to show Yost that much respect.

In 1952, he fined White Sox pitchers $25 for walking Eddie. But it did not help much. Sox pitchers paid a total $575 for the season. That’s 23 walks.

HIT BT PITCH

In the Yankees home opener on April 18, 1952 Yost hit Hall of Fame Yankee pitcher Allie Reynolds’ first pitch on a line to center for a hit. The Nats won, 3-1, behind Connie Marrero, disappointing an opening day crowd of more than 46,000. In the decisive 4th inning, Reynolds nearly escaped a bases loaded and nobody out situation. But he hit Yost with a pitch to force in a run to make it 2-0. The Chief, feeling Yost made no effort to get out of the way of the ball, angrily confronted Yost. “The next time I hit you with a pitch, it won’t be a slow curve in the back; it will be a fast ball between the eyes,” he said. Rattled, Reynolds walked the next batter to force in another run.

Yost was hit by a pitch 99 times in his career. Twice he was hit twice in a game. That’s 57th on the all time list.

THE END OF “THE STREAK”

On May 12, 1955, Mickey McDermott out dueled Herb Score, shutting out the Cleveland Indians at Griffith Stadium. The Senators won, 3-0. But for the first time in six years, Eddie Yost, sidelined by tonsillitis, was not at third base for Washington. It ended the longest current consecutive game streak in baseball at the time at 838 games. Tony Roig took over for Yost, going 1 for 4 and driving in a run. Roig did make an error.

(Hot Dogs were 20 cents at Griffith Stadium in 1952.)

POVICH IS ALSO A FAN

The veteran sportswriter Povich was a big fan and friend of Eddie Yost which may have influenced my affection for Eddie. I read his “This Morning” column regularly. Povich interjected himself, unabashedly, into a salary dispute before the 1953 season. From Povich’s “This Morning” column on Feb 24, 1953.

Ordinarily, it is none of my business, but when the parties concerned make news of their bickering they move smack into our domain, so what had been the private salary squabble of Eddie Yost and the Washington Senators is today’s topic…

Vice President Calvin Griffith of the Nats hints that Yost is already overpaid and will not get a penny, red or otherwise, beyond the latest offer.

Supposedly, Yost was drawing $17,000 last season, which is not to say that he was earning it with that .233 batting average he finally managed to assemble…

Griffith sent Yost a 1953 contract that called for no salary cut despite the player’s prolonged slump of 1952. He couldn’t find it in his heart to wield a cleaver on a fellow who was having his first poor season in the majors.

Did Yost embrace Griffith’s bountiful offer and bust a ballpoint putting his name to the contract? He did not. He put his name to a demand for a $4000 raise that produced a reaction just this side of apoplexy when it was noted by negotiator Griffith. “He’s crazy,” or words to that effect, said Griffith. “Lemme look at them batting averages again.”

Up in Ozone Park, N.Y. Yost, however, is letting his eye dwell on a few other figures. Who scored the most runs for the Washington team? Yost. Who got on base the most times? Yost. Who led the league in Walks? Yost. Who batted in 49 runs, only 15 fewer than the club’s cleanup hitter? Yost. Who gave the Nats the best third base job in the league? The same guy. And so Yost wants more of the club’s money. Not so much more, now, as originally. They are only $1000 apart today… Griffith says he won’t budge and Yost says he won’t budge wither… Somebody will budge, however, and Yost will play third base for the Nats again.

Yost already had one distinction to his credit. In 1950, when Ted Williams was the most-feared hitter in the league, Yost drew more walks than Williams. He has another distinction. He’s the only .196 hitter ever to be selected on the American League All-Star team. That happened last summer, a tribute to his ability to get on base and his superb fielding. Yost plays all the games -157 last year, including three ties. Not only that but who hit the most home runs (12) on the Washington club last season? Yost is the name…The fence is going to be 15 feet nearer this year, and Yost apparently would like to be paid for his potential.

DRESSEN DOES NOT CONSIDER YOST’S WALKS A VIRTUE.

In 1955 Manager Charlie Dressen, making a break with former Manager Bucky Harris’ use of Eddie as a leadoff hitter, wanted Yost to swing more. “I’m going to drop Yost down,” said Dressen.

He’ll be a better hitter if he’s not trying to get that walk, and my schooling in this game has been that you can drive in more runs with base hits than with walks.”

“Nobody complained in 1951 when I hit .283,” said Yost, or in 1950 when I finished up with .295. I was drawing just as many walks those years and they didn’t say I was walk crazy. Anyway, Bucky Harris never complained when I drew those walks. I’ll still get my share of walks but I’ll be swinging too. The hits I want are through the middle… Shortstops and Leftfielders will discover they can’t crowd me. I am going to make them play me honest and if they do then I’ll like my batting average.”

Yost missed 32 games in 1955 but still had 95 walks and an on base percentage of 407.

SO LONG WALKING MAN – POVICH LAMENTS TRADE.

On December 6, 1958, Yost, shortstop Rocky Bridges, and outfielder Niel Chrisley were traded to the Detroit Tigers for Reno Bertoia, Ron Samford, and Jim Delsing. Shirley Polish wrote:

There will be a new tenant at third base in Griffith Stadium next season with Eddie Yost’s 12 year lease having run out. Calvin Griffith decided not to renew… Griffith’s hope is that Bertoia, at 23, nine years younger than Yost, will be the third baseman Yost used to be. That is asking considerable and the Nats would settle for a mite less and still regard third base in excellent hands…

If Yost wasn’t the finest third baseman in the American League for most of 10 years he was close to it…For those Washington fans who for most of a decade admired the big leaguish performance of Yost, he later provided heartbreak. Unaccountably, he began slowing up a couple of years ago at the age of mere 30. The plays he didn’t make, the hits he didn’t beat out, were agonizing to those who had thrilled to what used to be his perfection. . There are explanations for that, too. He had simply given too much to the club in that ridiculous Iron Man effort that kept him in the lineup for more than 800 consecutive games, many of which were on legs that were bruised, blackened and taped, on days when he should have been on the bench.

On many a rag tag, bobtail Washington team, Yost was a stand-out big leaguer, the perfect model of major league player from the tilt of his cap to the subtle swagger as he flicked off his glove after making a play that ended the inning.

The record shows that Yost was an excellent hitter in the high .280s in his early years with Washington then lapsed into .230 and .240 averages. Why? They asked him that once, and he said honestly that pitching had improved. “Those sliders they’re throwing now,” he said. “I’m finding them harder to hit.”

FINISHING UP AS A PLAYER, RETURNING TO WASHINGTON

After 14 seasons with the Senators, Yost played two seasons (1959-60) with the Detroit Tigers and two more (1961-62) with the Los Angeles Angels. After a brief stint as a playing coach with the ’62 Angels, Yost returned to Washington as the third-base coach of the second Senators franchise, under his old teammate and good friend, Mickey Vernon. When Vernon was replaced by Gil Hodges, Yost briefly served as interim manager (losing his only game as manager – on May 22, 1963) and then continued on Hodges’ Washington staff through 1967.

IRONMAN RECORD FALLS

On April 21, 1966 as the Braves tripped the Phils, 5–4, Eddie Mathews set a major-league record by playing his 2009th game at third base, topping Eddie Yost’s mark.

LEAVING WASHINGTON AGAIN

When Hodges returned to New York as Manager of the New York Mets in 1968, he took Yost with him. Eddie served nine seasons (1968-76) as the Mets’ third-base coach, and was thus a part of the “Amazin’ Mets'” World Series win in 1969 and the NL championship in 1973. (Hodges died suddenly from a heart attack in 1972).

Synonymous with the Mets of that period: Eddie coaching at third, clapping his hands and Yogi Berra coaching at first was very popular with Mets fans. They would mimic Yost’s gestures waving around third. He knew the strengths and weaknesses of all the outfielders in the National League. Rarely was a Met runner thrown out at the plate.

Yost then continued his career as a third base coach with the Boston Red Sox for another eight seasons (1977-84). As a third base coach, Yost was popular in Boston also. In September 2004, Presidential candidate John Kerry was asked who his favorite Red Sox of all time was. He replied, “Eddie Yost.”

Eddie Yost, of course, never played for the Boston Red Sox. But he was their third base coach and he was there with Manger Don Zimmer when Bucky Dent hit that historic home run in that 1978 playoff.

And anyway, for a Nats fan, it was nice to see The Walking Man get mentioned during a Presidential race.

His major league career spanned 41 years as a player and coach.

Yost wrote me recently from his home in Wellesley, Massachusetts. “I feel very fortunate having been part of baseball for those many years. It was something I dreamt of as a child,” he said.

It is fitting that I end this piece with a Phil Wood salute – Phil’s signature radio sign off, “E E E ddie Yost.”