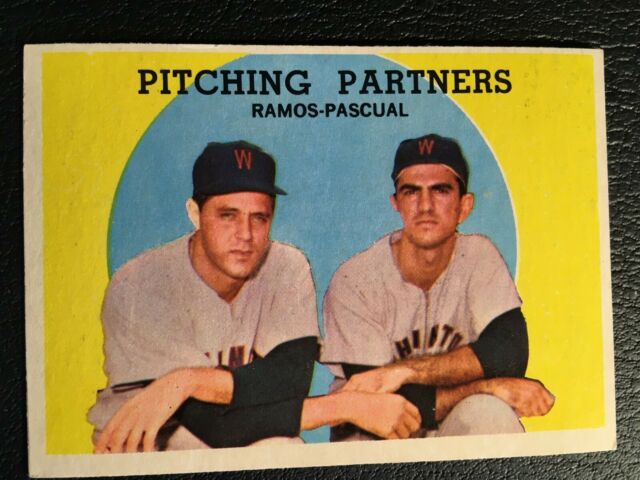

RAMOS AND PASCUAL -PITCHING PARTNERS

By Jeff Stuart

I once owned a 1959 Topps Baseball Card #291 labeled, “Pitching Partners-Pedro Ramos-Camilo Pascual.” Somewhere along the way, I lost it. Even though it is only worth about $3.50 today, I would readily pay that for it. Certainly, it is worth more than that to an old Senators fan. The two were my earliest baseball heroes. Though the team finished last for 4 of their 6 seasons together in Washington, the club’s attendance improved every year during the last six seasons of the Ramos and Pascual era. That increase in attendance was in large part due to the charismatic Cubans duo.

JOE CAMBRIA

Owner Clark Griffith, and later, his adopted son, Calvin, both embraced penny-pinching. In the 1930’s Clark hired “Uncle Joe” Cambria, an Italian-born laundry man from Baltimore to scout cheap talent in Cuba. Over the next 26 years, he signed an estimated 400 Cubans to the Senators organization. The cost to the Senators was ridiculously low by the standards of the day. Pascual was signed for $175. Ramos was originally brought in, at no cost, just to pitch batting practice. Carlos Paula, Connie Marrero, Jose Valdivielso, Julio Becquer, Zoilo Versailles, and Tony Oliva were other “Papa Joe” signups.

Cambria eventually acquired the minor-league Havana Cubans, a string of bars, and a restaurant called the “Triple A.” He lived at the restaurant that was just beyond the center field scoreboard of Havana’s Gran Stadium. From his little empire Cambria eventually funneled Cuban talent to all major league teams. (1) Joe Cambria wanted to sign me for $150 a month in Cuba in 1953,” Ramos told George Minot of the Washington Post. “But I told him I was used to living better than that and to show him, I invited him to my home 100 miles from Havana. He agreed and gave me a $125 raise.” (2) Camilo, “Little Potato,” was original recommended to the Senators by his older brother, Carlos, “Big Potato”, Pascual who was also recruited by Cambria and pitched briefly for the team in 1950.

THE “PALM” AND THE “CALM”

Ramos was slightly taller at 6 feet to Pascual’s 5′ 11″ and both weighed about 185 pounds. Pascual, born January 20, 1934, was slightly older and the son of an air conditioning engineer in Havana. Ramos, the son of a tobacco merchant in Pinar Del Rio, was born on April 28,1935. To Washington fans the two Cuban stars were always thought of as a package deal, and seemed almost interchangeable.

By most descriptions, the 1950s Cuban Senators were a loose and entertaining bunch that included Connie Marrero, Carlos Paula, Julio Becquer, Jose Valdievielso, Zolio Versalles, Pedro Ramos and Camilo Pascual. Roommates on the road, Pedro, and Camilo were young and single and free until 1959. That was the year, Pascual married Raquel Ferrero, and Ramos was engaged to Miriam Morales.

Ramos was often accused of throwing a spitball. He called it the Cuban Palm Ball. In a game in Cleveland in 1962, umpire Ed Runge, suspicious that Ramos was rubbing the ball on a tobacco stain on his pants, ordered him into the clubhouse to change pants, but it did not end there. A few pitches later, Runge had him leave the field again, this time to change shirts. Finally, the unusually patient umpire requested that he change his cap. When Ramos donned a batting helmet as a replacement, Runge felt that he was making a mockery of the situation and ejected him. (3)

The outgoing and competitive Ramos often challenged opposing players to a foot race. He beat Philadelphia’s Richie Ashburn, Cincinnati’s Don Hoak, as well as Reds’ bonus baby Bobby Heinrich, a high school sprint champion. Not as daring, of course, was the time he challenged the speed-impaired catcher, Clint Courtney, to a race in 1956. Courtney, like Mantle to a number of previous challenges, declined. The speedy pitcher goaded Courtney with an advantage. Ramos was to race home from the centerfield flagpole at Griffith Stadium while the catcher was to race home from second. Always seeking a dare, Pete once bet a teammate that he could throw a ball and hit the roof of the Astrodome. He tried but did not succeed.

Camilo Pascual was as quiet of the field as Ramos was gregarious. Hence the nickname, “The Calm.” (4) He preferred conservative American fare like TV Westerns, Frank Sinatra, and Nat King Cole. Ramos had a more romantic if charicature like perception of American culture and usually dressed flamboyantly, frequently sporting a western hat and cowboy boots. (5) Yet they enjoyed each other’s company and their joint adventures were often humorous.

“Perhaps Camilo Pascual needs glasses,” wrote columnist Bob Addie, “ His buddy, Pedro Ramos, was telling the story of both hunting in Cuba this winter. Camilo shot a duck but it turned out to be a farmer’s horse. Pascual had to pay damages.” (6) “Camilo is like my brother,” Ramos told Joe Durgan of the New York Times in 1965. (7) “Ramos and Pascual worked together like a bicycle built for two,” wrote Bob Addie of the Washington Post. (8) Their personalities carried over onto the field.

“Pascual was the type who would forget about the game with the last out,” wrote David Gough in “They’ve Stolen Our Team.” Gough went on to explain, “While Ramos was a brooder who would relive every pitch and agonize over his mistake, Pascual was a believer in the law of averages, that things had a way of balancing out over time. Ramos, on the other hand was very superstitious and always on the lookout for ‘good luck’ charms.” (9)

Pascual was meticulous, slow worker and nothing rattled him. He had a great fastball complemented with a spectacular curve. But Ramos was a fast worker. He had great control and a good fastball. With a gambler’s guile, he challenged hitters, and his best pitch was always his controversial “palm” ball. On the field both were competitive in their own ways.

Washington owner, Calvin Griffith, was never one to loathe parting with players for an influx of ready cash, but he was protective of his talented Cuban pair. Being told in May of 1960 that a struggling Ramos wanted to go to New York where he could be with a winner, he emphatically told reporters “The Yankees have no chance of getting him or Pascual.” (10)

PASCUAL IN WASHINGTON

Pascual arrived first in Washington in 1954 at the tender age of 20 years and three months, the youngest player in the league. Camilo debuted on April 15, 1954, in relief of Bob Porterfield as the team lost 6-1 to the Red Sox at Fenway Park. As a reliever, Camilo posted a 4-7 mark in 1954 with three saves and a 4.22 era. Still in the bullpen in 1955, he was 2-12 with a 6.14 ERA. Tapped to start the 1956 opener, he lost to the Yankees and Don Larsen, 10-4. He led the league, in homers allowed that season with 33, and won only 8 while losing 18. The maturing Camilo won 17 games for the last place ‘59 Senators and posted a 2.64 ERA. He developed his wicked sidearm curve to complement his fastball, as he led the league with seven shutouts, and seventeen complete games, while pitching 238 innings. Pascual, now an American League All-Star, became the first Washington starter to post a winning record since Dean Stone went 12-10 in 1954.

On April 18, 1960, Pascual started in the last American League opener for the old Senators before President Eisenhower. He struck out 15 Red Sox batters, tying Walter Johnson’s club record as Washington won over Boston, 10–1. A Ted Williams homer that sailed far over the centerfield wall and into the clump of trees beyond, accounted for the only Boston run. Pascual went 12-8 for the Senators in their last season in DC, 1960, and was again named an All-Star.

RAMOS

Ramos arrived in 1955 season, debuting on April 11, 1955. Like Pascual, his debut came in relief of Porterfield. The team won this time, 12-5, defeating the Orioles, at Griffith Stadium. Like Pascual, Ramos was used primarily as a reliever in his first year. Ramos posted a 5-11, mark with five saves and a 3.88 ERA. He had the dubious distinction of leading the league in hit batsmen with 11. Ramos got a lot of starts with Washington from 1956 to 1960, winning 10 or more games each year, peaking at 14 wins in 1958 when he hurled 4 shutouts, third in the league. But his only winning season in Washington was 1956 when he finished 12-10 for a 7th place team. Ramos got the start in the 1958 opener, posting a 5-2 win over the Red Sox. He tapped for the opener again in 1959 as well, defeating Baltimore, 9-2. Ramos, as a substitute for Pascual, was named an American League All-Star in 1959. Neither pitched in either of the two games that season.

WINTER BALL – CIENFUEGOS

For the entire time they were together in Washington they also pitched together during the winter months for Cienfuegos of the Cuban Professional League. Cienfuegos, which might have been a better them than the Senators, won League Championships in 1957, 1960, and ‘61. Cienfuegos represented Cuba in the prestigious Caribbean Series in 1956 and again in 1960, beginning and ending a string of five straight Cuban victories. Notable Major League players who participated in the series during this period included Luis Aparacio, Orlando Cepeda, Roberto Clemente, Willie Mays, former Senator, Conrado Marrero, Minnie Minoso, and Don Zimmer. In February 1956, at the Caribbean Series in Panama City, Panama’ Cienfuegos posted a 5-1 record. Pascual and Ramos each won two games. In the1959 series, in Caracas, Venezuela, Almendares, representing Cuba, added Pascual to its roster. The overpowering Cuban pitching staff already featured Orlando Pena and Mike Cuellar. In February 1960 in Panama City, Panama: Cienfuegos finished a 6-0 sweep to give a Cuban team its fifth straight series championship. Pascual won two games, including the Series clincher, a 2-0 shutout of Puerto Rico. Ramos also won a game.

Ramos was twice the leading pitcher in the Cuban League, winning 13 and losing 5 in 1955-56 season, and winning 16 and losing 7 in 1960-61. His teammate and partner, Pascual, was twice the leader in the intervening years going 15-5 in 1956-57, and repeating the 15-5 performance in 1959-60. Each won the League’s Most Valuable Player Award as well. Pascual won it for the1955-56 season, while Ramos closed out the era, taking the last MVP award in 1960-61. (11)

AN AUTOGRAPHED BALL AND THE END OF THE CUBAN CONNECTION

During the winter season in 1960, Ramos and Pascual had obtained a ball signed by Fidel Castro for Washington owner Calvin Griffith. (12) But after 1961, the effective Ramos/Pascual winter pitching partnership was abruptly dissolved by politics when Castro declared Cuba’s entire 83-year-old professional league defunct. Two dozen major-league players, including Becquer, Pascual, Luis Tiant and Tony Perez, were blocked temporarily from returning to the U.S. and ended up in Mexico scrambling after U.S. visas. Ramos had assumed ownership of his father’s cigar factory during these years. His picture was on the band of every “El Gladiator” cigar, but Castro expropriated the company and Ramos’ other business venture in Cuba ended as well.

THE END IN WASHINGTON

Pedro, now often Americanized as “Pete,” led the league in starts again in 1960 with 36. Over a 6 game stretch during that season Ramos yielded only 16 runs but lost them all. He went 11-18 with a respectable 3.45 era. Since Pascual opened that last season in Washington, it was fitting that his partner, Ramos, closed it out. On October 2, 1960, Ramos took the loss as Washington dropped a 2–1 decision to Baltimore in the last game ever played by the original franchise Senators.

Although the Senators finished last in four of their last six seasons in Washington, the club that departed Washington for Minnesota was a team on the rise. They finished fifth and drew 743,404 fans in their final season, which was certainly respectable for the time. The addition of veteran catcher Earl Battey, who won a Gold Glove in 1960 helped. And youngsters like outfielder Bobby Allison, the 1959 American League Rookie of the Year, and left-handed pitchers Jim Kaat and Jack Kralick made the team better and certainly more interesting to watch than it had been in years.

MINNESTOTA AND THE END OF THE PARTNERSHIP

Having pitched the final game for the franchise in Washington, Ramos got the April 11, 1961 received the honors for the opening day assignment for the Twins. He defeated Whitey Ford as he shut out the Yankees 6-0 at Yankee Stadium. Pascual got the nod to pitch the home opener, the first game ever at Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium on April 21, 1961. Pascual did not take the loss as the Twins lost 5-3 to the new expansion team in Washington. Camilo went 15-16 in his first season as a Twin but he led the American League with 8 shutouts and 221 strikeouts. It was the first of three straight seasons he would lead the American League in that category. Ramos won 11 but suffered the ignominy of losing 20 as the team slipped to seventh place. On April 2, 1962 Ramos, “El Gladiator,” was traded to the Cleveland Indians for Vic Power and Dick Stigman. The six-year pitching partnership with the Senators/Twins and Cienfuegos was now dissolved.

How important were they as teammates on the Senators and Twins? There were no championships to be won. The club, though improving, was always weak, yet they were the dominant pitchers on the team. Ramos led the franchise in innings pitched every year from 1957 to 1960. He had ten or more wins every year from 1956 to 1960 and was the only starter to post a winning record in 1956. Pascual led the team in wins in 1959 and 1960.

PASCUAL ALONE IN MINNESOTA

With a more powerful lineup in Minnesota, Pascual did eventually prosper.

He posted 20-11 and 21-9 records in 1962 and 1963 while leading the league in strikeouts both years. In the second 1961 All-Star Game he pitched three hitless innings and fanned four, baffling NL hitters with his dazzling curve. Pascual got two more opening day assignments in Minnesota. The Twins lost to the Indians and Mudcat Grant, 5-4, at Metropolitan Stadium on April 9, 1963, and defeated Mudcat and the Indians, 7-6 on April 14, 1964 in Cleveland. In 1964, Camilo won 15 games with a respectable 3.30 ERA while striking out 213.

In 1965 the Twins won the American League pennant but lost to the Dodgers in the World Series. Camilo only went 9-3 on the year as arm miseries reduced him to a spot starter. The Twins beat the “veteran” Dodger pitchers Drysdale and Koufax in their first two games of the series in Minneapolis. But Claude Osteen, a former expansion Senator, beat Pascual in game three, throwing a five hit, 4-0 shutout in LA. Pascual gave up a two run single to Johnny Roseboro in the fourth that proved pivotal in the series. Drysdale and Koufax posted victories in games 4 and 5. The Twins, back home in Minnesota, won again in game 6 behind Mudcat Grant, 5-1, but the Dodgers took the final game, 2-0 behind Koufax again.

RAMOS IN CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK

Pete went 10-12 for sixth-place Cleveland in 1962, posting a 3.77 ERA and two shutouts. He then struck out 169 batters while posting a 9-8 mark with the Indians in 1963. The Indians finished fifth that year. Meanwhile, Pedro’s old partner and the Twins finished 2nd in 1962 and 3rd in 1963. Ramos finally got his chance to play for a winner when the Indians traded him to the Yankees on September 5, 1964 for Ralph Terry, Bud Daley, and $75,000. Assuming a relief role in a tough pennant drive he saved 8 games and posted a 1.25 ERA. He was the New York’s bullpen stopper for the next two seasons, with 19 saves in 1965 and 13 in 1966. But Yankee manager Johnny Keane put an end to Ramos’ beloved foot race challenges. “I was losing a step, anyway,” said Pete. (13) Though no Yankee won a starting position in the voting for the 1965 All-Star game, catcher Doc Edwards, a Ramos roommate on the road in Cleveland and New York, lobbied for Pete’s selection. Mantle, Elston Howard, Bobby Richardson, and Mel Stottlemeyer eventually were selected by Al Lopez to represent the proud but aging Yankees.

PASCUAL RETURNS TO WASHINGTON

On December 3, 1966, Minnesota traded Pascual and Bernie Allen to the expansion Senators in return for pitcher Ron Kline. Still popular in Washington, Camilo became the first pitcher for the expansion Senators to post back to back winning seasons. He was 12-10 in 1967 and 13-12 in 1968. Pascual was the only starter with a winning record in his two full seasons there. On April 10, 1968 he lost the 1968 Washington season Opener, 2-0, to Dean Chance and the Twins.

Pascual got the opening day assignment again on April 7, 1969 at RFK Stadium, before 45,000 fans, which included President Nixon who was excited by the managerial debut of Ted Williams. Camilo took the loss as the Yanks spoiled the day by winning, 8-4. Camilo’s last appearances as a Senator were on July 9, 1969 at Fenway Park. He was used as a pinch runner in both games of a doubleheader, scoring his last run in the first game

REUNITED IN CINCINNATI

The fading Cuban pair missed by a year of being reunited with the Senators in Washington, but they did join forces again for half a season with the Cincinnati Reds. On June 10, 1969, Ramos signed as a Free Agent with Reds. Then, on July 7, 1969 the Reds purchased Pascual’s contract from the Senators. Camilio pitched in 5 games for the Reds, starting once. He threw just 7 1/3 innings.

Ramos went 4-3, pitching 66 innings in 38 games, all in relief. Though his fast ball was largely history, he still struck out 40. On July 15th, Ramos hurled a scoreless inning against the visiting Cubs in his first appearance, but Chicago won 5-4. Perhaps his most dominant performance came on June 17, at Candlestick Park. He struck out 5 in two innings, but Hall of Famer Juan Marichal, who struck out 8 in 9 innings, shut the Reds out, 4-0.

The pair appeared in four games together with Cincinnati. On July 11, 1969, the Astros routed the Reds, 13-2, at the Astrodome. The Cubans gave up 8 runs between them in the first appearance as a Red for Camilo. On July 16th at Crosley Field, the Reds beat the Atlanta Braves, 10-7. This time the duo was successful at closing it out. Pascual gave up a run in 1 and a 1/3 innings while Ramos earned the save allowing no runs in the final 2 and a 1/3. They were successful again on July 19th at Crosley Field. After Pascual hurled a scoreless 8th, Ramos Pitched 3 scoreless innings to pick up his 3rd win. The Reds, trailing 9-0 after 5 1/2 inning, had rallied to defeat Houston, 10-9, in 11 innings.

On Sunday, August 3, in a slugfest at Connie Mack Stadium in Philadlephia, the Reds prevailed, 19-17. Pascual, the starter, gave up three runs in 1/3 of an inning. Ramos came on in the 6th, allowing 4 runs in 2/3 of an inning, but none of the 11 pitchers on either team distinguished themselves that day. It was the last appearance by Pascual in a Cincinnati uniform. On July 17 at Crosley Field, in his only solo Reds appearance without Pedro, Camilo closed out the game with two scoreless innings of relief. But Cincinnati was trailing 12-2 to Atlanta at the time and the game ended that way.

Together again, Camilo and Pete were probably more important to each other than they were to Cincinnati. At 89-73, the Reds finished third under manager Dave Bristol in 1969. But with Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, Tony Perez. Clay Carroll, and Gary Nolan already on board, and Sparky Anderson’s set to arrive in 1970, the “Big Red Machine” was about to roll. The Cuban duo just missed being a part of that baseball dynasty.

RAMOS RETURNS TO WASHINGTON

Ramos also briefly returned to the Senators roster in the spring of 1970 after winning 15 games in Mexico during the preceding winter, hurling 18 complete games there. President Nixon who, had watched Ramos win two opening games, called Pedro at his Miami home to express the hope he would see him again in Washington. (14) When he reported Pedro was given the number 17, which had been worn the previous year by his old friend, Camilo. Ramos said he placed no special significance on the number. “Numbers don’t help you win games. When I was with the Yankees they asked my preference in numbers. I asked for 3 and was turned down.” (15) Though his return was largely symbolic, he pitched 4 innings while giving up 3 runs against the Yankees at RFK on April 23, 1970 as New York won 11-6. His final game was on April 25th at RFK. He pitched the top of the ninth, striking out 2, and giving up a solo homerun to fellow Cuban Joe Azcue as the Angels won 5-3.

CAMILO IN CLEVELAND

Camilo finished his career with the Cleveland Indians in 1971, the last season the expansion Washington Senators existed. His last start was on April 20th at Fenway Park when he lost to the Red Sox, 4-1. He posted his last win on April 28 in relief of Sam McDowell in Anaheim, pitching a scoreless 8th inning, giving up one hit and striking out one. Cleveland won 3-2. His last appearance came on May 5th when he pitched the final two innings in a 4-2 loss to Kansas City, giving up no runs, one hit, one walk, and striking out two.

A DURABLE PAIR.

During their 7 consecutive years together in Washington and Minnesota, Pedro Ramos and Camilo Pascual pitched an average of 203 innings and made an average of 27 starts a year. Ramos peaked a 274 innings in 1960, and Pascual hurled 252 innings in 1961. Camilo led the league in complete games in 1959 with 17 while Pedro led the league in complete games in 1960 with 14. Ramos led the league in games started in 1958 and 1960 peaking at 37 starts in 1960. ()

The highest reported annual salary that Pascual ever received was $52,000 from the Reds in 1969. The highest reported annual salary Ramos ever received was $25,000 in 1965 and 1966 from the New York Yankees, though he probably earned more than that with the Reds in 1969. Pound for pound and by the inning these two were, throughout their careers, an incredible bargain.

POSTSCRIPTS

THE PARTNERS, MICKEY AND HOMERUNS

“Washington meant so many good memories,” Mickey Mantle told Tom Boswell of the Washington Post in 1985. (16) as he was promoting his book, “The Mick”. “Pedro Ramos and Camilo Pascual would laugh and rag each other about which gave up the longest home runs to me. Mantle hit 12 career homers off Pedro and 11 off Camilo. He only hit more, 13, off Early Wynn.

“I hit two home runs into the tree beyond center field in old Griffith Stadium off Pascual, and Ramos is up waving a towel at Pascual while I’m rounding the bases. Later that year I hit one off the facade in Yankee Stadium off Ramos, and as I’m rounding third I see Pascual waving the towel at Ramos.” Ramos was reported to be Mantle’s favorite pitcher. But in truth he hit long homers off both. On April 17th, 1956, opening day in Washington, batting left handed, Mantle hit two tape measure blasts of over 500 feet off Camilo. But in tribute to “the Calm,” he considered it a major feat. “I hit those off Camilo Pascual,” he said, “one hell of a pitcher.”

Then, on May 30, 1956, following a Ramos knockdown pitch in the first game of a doubleheader, Mantle hits a blast that came within 18 inches of leaving Yankee Stadium. The ball caromed off the upper-stand facade of the third deck, about 396 feet from home plate. Estimates are that the ball could have traveled more than 600 feet. Estimating the length of Mantle homers was not an exact science, however, Mantle told the Daily News between games of the doubleheader, “It’s the hardest ball I ever hit left-handed.” Some published articles suggest this blast came off Pascual. Perhaps the confusion is because he hit a 500-foot homer in the second game against Camilo to help propel the Yankees to a 12-5 win and a sweep. (17)

On May 2, 1961 The Yankees, in their first game in Minnesota after the Senators had left Washington, topped the Twins, 6–4. Mickey Mantle’s grand slam in the 10th inning off Pascual, is the big blow. A change in location had not changed the usual result. Later in the season, on August 6, 1961, Mickey Mantle led the Yankees to another doubleheader sweep of the Twins, going 5-for-9 with three home runs and a double. In the opener, Mantle blasted two home runs off Ramos. But Mantle could do damage with speed too. On May 9, 1958, in the first night game of the year at Yankee Stadium, Mantle broke a 2–2 tie with the Senators in the 3rd inning with an inside-the-park solo homer off Ramos. New York won 9-5. Ramos, who was very fast in his own right, would always challenge the speedy Mantle to a race, and Mickey would always decline.

PEDRO AND TED

Ed Linn’s biography, “Hitter, the Life and Turmoils of Ted Williams,” (18) tells the story of Ramos striking out the great Ted Williams in 1955. Elated, Pedro ventured into the Red Sox locker room after the game in Washington and asked Ted to autograph it. After protesting, “I don’t sign balls I struck out on, Willams said, “Sure, give me the ball, I’ll sign it for you.” But in the next game that Ramos pitched against the Red Sox at Fenway, Williams homered deep to right. As he began his homerun trot around the bases, he yelled to Ramos, “If you can find that sonofabitch, I’ll sign it, too.” The story is related again in David Halberstam’s “Teammates.” (19)

Footnotes:

(1) Welch, Matt, ESPN Page2 web page, The Cuban Senators, Oct 20, 1999.

(2) Boswell, Tom, The Washington Post, July 23, 1985, p. B1,B6

(3) Linn, Ed. Hitter: The Life and Turmoils of Ted Williams. New York. Harcourt Brace. First Harvest Books Edition , 1994. p. 189 l. 16-26.

(4) Halberstam,David. The Teammates. New York. Hyperion ,May 14, 2003, p. 109, l. 3-18.

(6) Gough, David: They’ve Stolen Our Team. Alexandria, VA. D.L. Megbec Publishing, p.69. l. 29.

(7) Gough, David: They’ve Stolen Our Team. Alexandria, VA. D.L. Megbec Publishing, p.69. l. 21-25.

(7) Gough, David: They’ve Stolen Our Team. Alexandria, VA. D.L. Megbec Publishing, p.81. l. 18-26.

(8) Strauss, Lewis L. Secretary, U.S Department of Commerce. Science and Technololgy. SF-59-10. Washington D.C. March 29, 1959. National Institute of Standards and Technology web site.

http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/centennial/curverelease.htm

(9) Lenehan, Michael The Last of the Pure Baseball Men. Atlantic Monthly.

August, 1981 ; Volume 248, No. 2; p. 35-49.

(10) Addie, Bob. The Washington Post, March 14, 1959

(11) http://www.cubanball.com

(12) New York Dailey News. Mickey nearly leaves the yard #45 Classic Moment. May 30, 1956.

http://www.nydailynews.com

(13) Addie, Bob. The Washington Post. Full Speed Ahead. April 10, 1970. p. D2.

(14) Minot, George. The Washington Post. Senators Sign Ramos to $21,000 Contract. March 31, 1970. p. D1.

(15) Durso, Joe. The New York Times. Sports of the Times. El Gladiator. July 4, 1965. p.S2.

(16) The Washington Post. Ramos is Gay Caballero of Cubans But Roomie Pascual is Quiet Type. July 19, 1959. C3

(17) Addie, Bob. The Washington Post. Senators win Orioles, 2-1, March 23, 1960, C1.

(18) Mantle, Mickey with Gluck, Herb. The Mick . New York. Berkeley Publishing. Doubleday. Jove Books, April 1, 1986. p. 137. l. 25-26.

Bibliography.

Linn, Ed. Hitter: The Life and Turmoils of Ted Williams.New York. Harcourt Brace. First Harvest Books Edition , 1994.

Halberstam,David. The Teammates. New York. Hyperion ,May 14, 2003

Mantle, Mickey with Gluck, Herb. The Mick . New York. Berkeley Publishing, Doubleday. Jove Books, April 1, 1986.

Gough, David: They’ve Stolen Our Tean. Alexandria, VA. D.L. Megbec Publishing

Hartley, Jim Washington’s Expansion Senators. Germantown, MD. Corduroy Press. 1997

Halberstam,David. The Teammates. New York. Hyperion ,May 14, 2003

Strauss, Lewis L. Secretary, U.S Department of Commerce. Science and Technololgy. SF-59-10. Washington D.C. March 29, 1959 National Institute of Standards and Technology web site.

http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/centennial/curverelease.htm

Baseball Library Web Page. http://www.baseballlibrary.com

Baseball Almanac Web Page. http://www.baseball-almanac.com http://www.baseball-almanac.com

Baseball Reference Web Page. http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams

The Last of the Pure Baseball Men by Lenehan, Michael Article in Atlantic Monthly

August, 1981. Reprinted in Before the Dome: Baseball in Minnesota When the Grass Was Real (1993) by Dave Anderson (p.121(18)

The New York Daily News. Mickey nearly leaves the yard #45 Classic Moment. May 30, 1956

http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/story/75653p-69910c.html

Addie, Bob. The Washington Post.

Minot, George. The Washington Post.

Boswell, Tom. The Washington Post.

Durso, Joe. The New York Times.